In last Monday’s City Council hearing in front of the Public Health and Human Services Committee, testimonies from roughly 30 individuals in the debate over safe injection sites were heard.

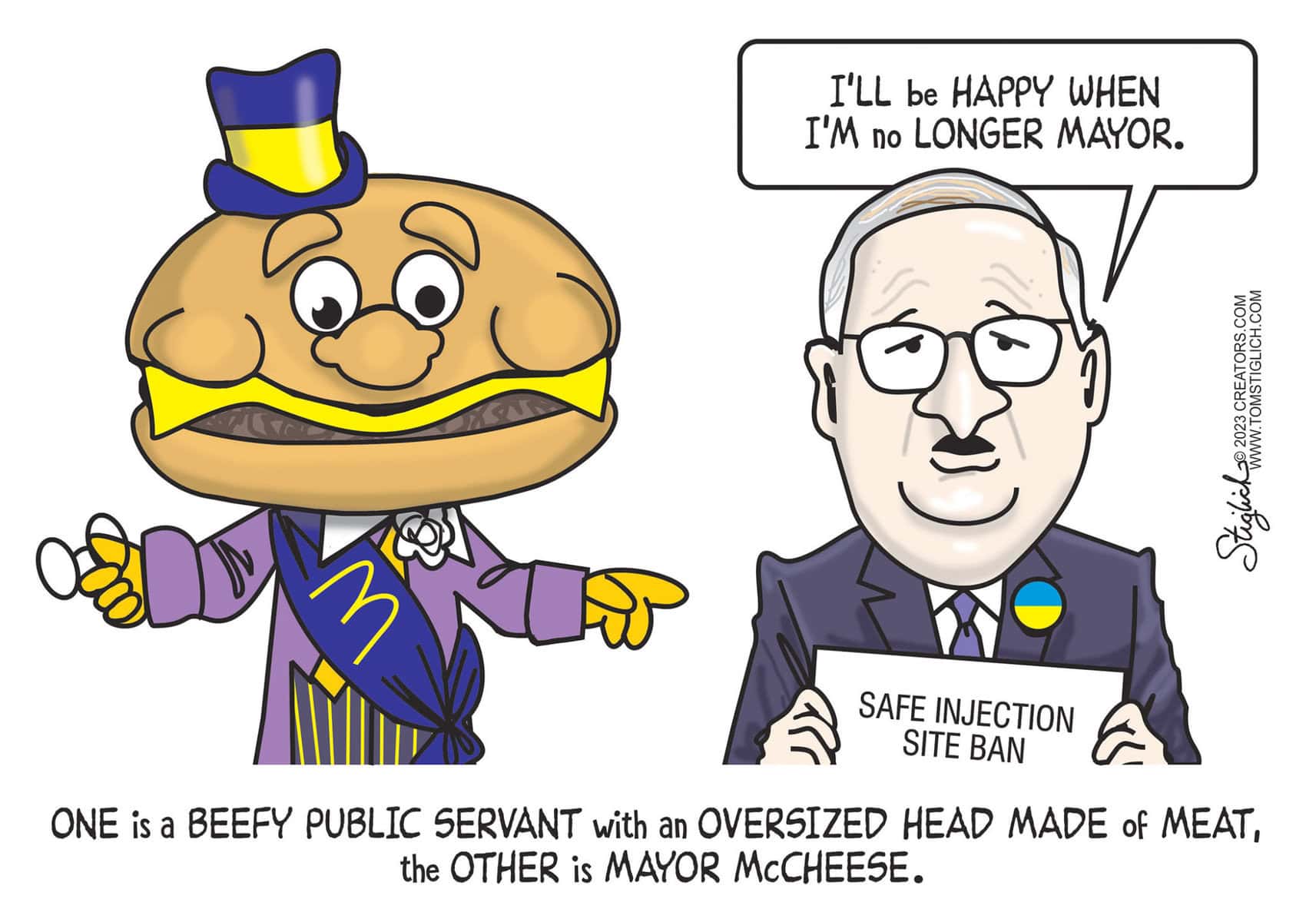

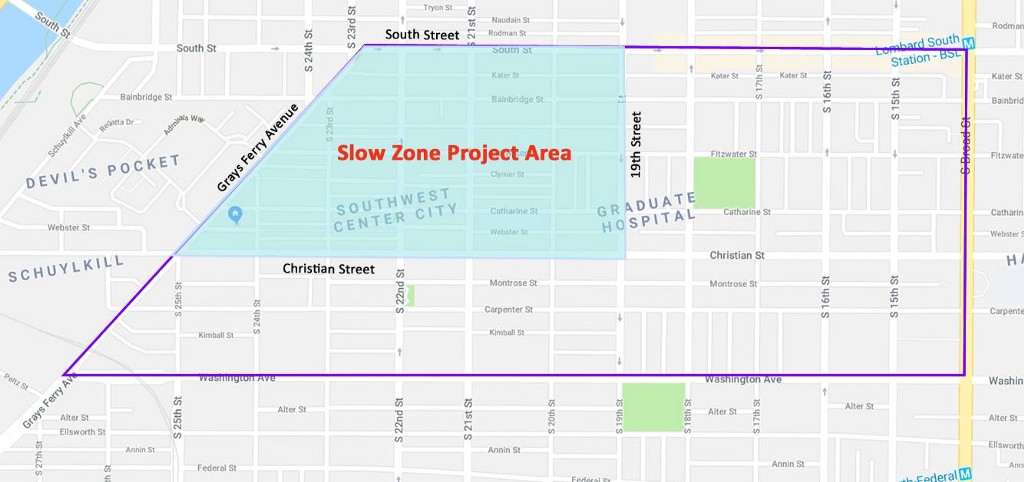

The majority of these testimonies spoke in favor of the bill introduced by Councilmember David Oh, which would virtually ban safe injection sites in Philadelphia, with voices coming predominantly from city residents and civic leaders railing against Safehouse’s lack of communication with the South Philadelphia community before its decision to open a safe injection site inside of South Philly’s Constitution Health Center.

But not all of the day’s testimonies came from city residents. Four, in fact, came from either credentialed medical professionals or academics who study public health.

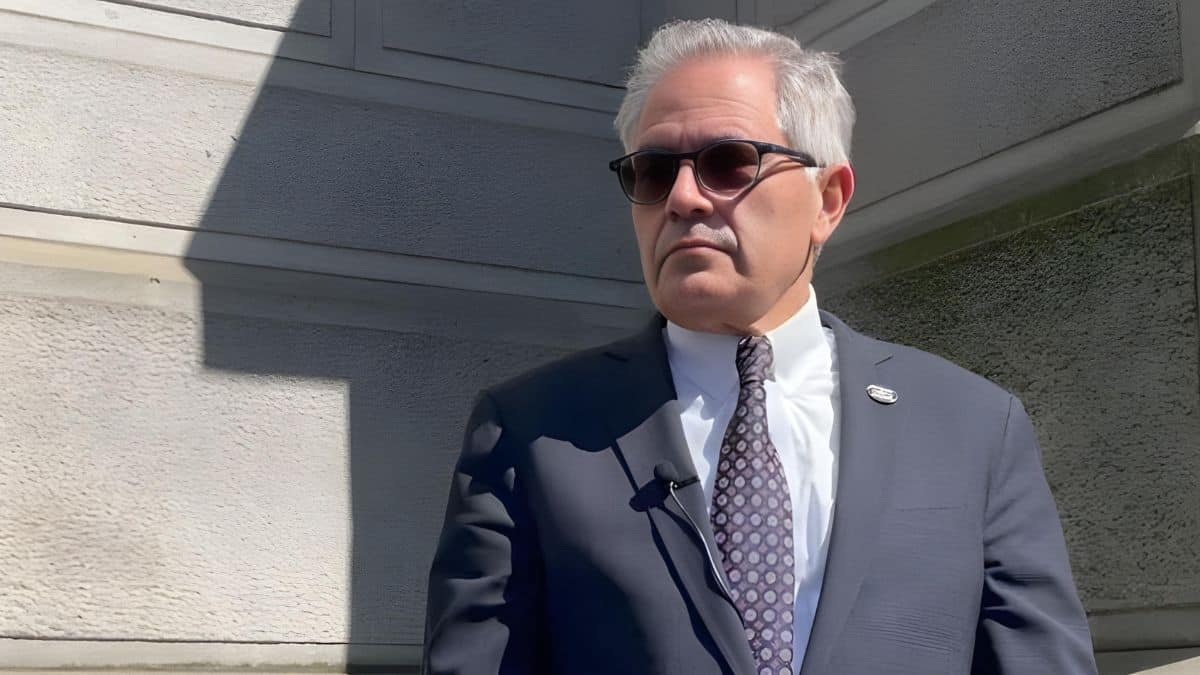

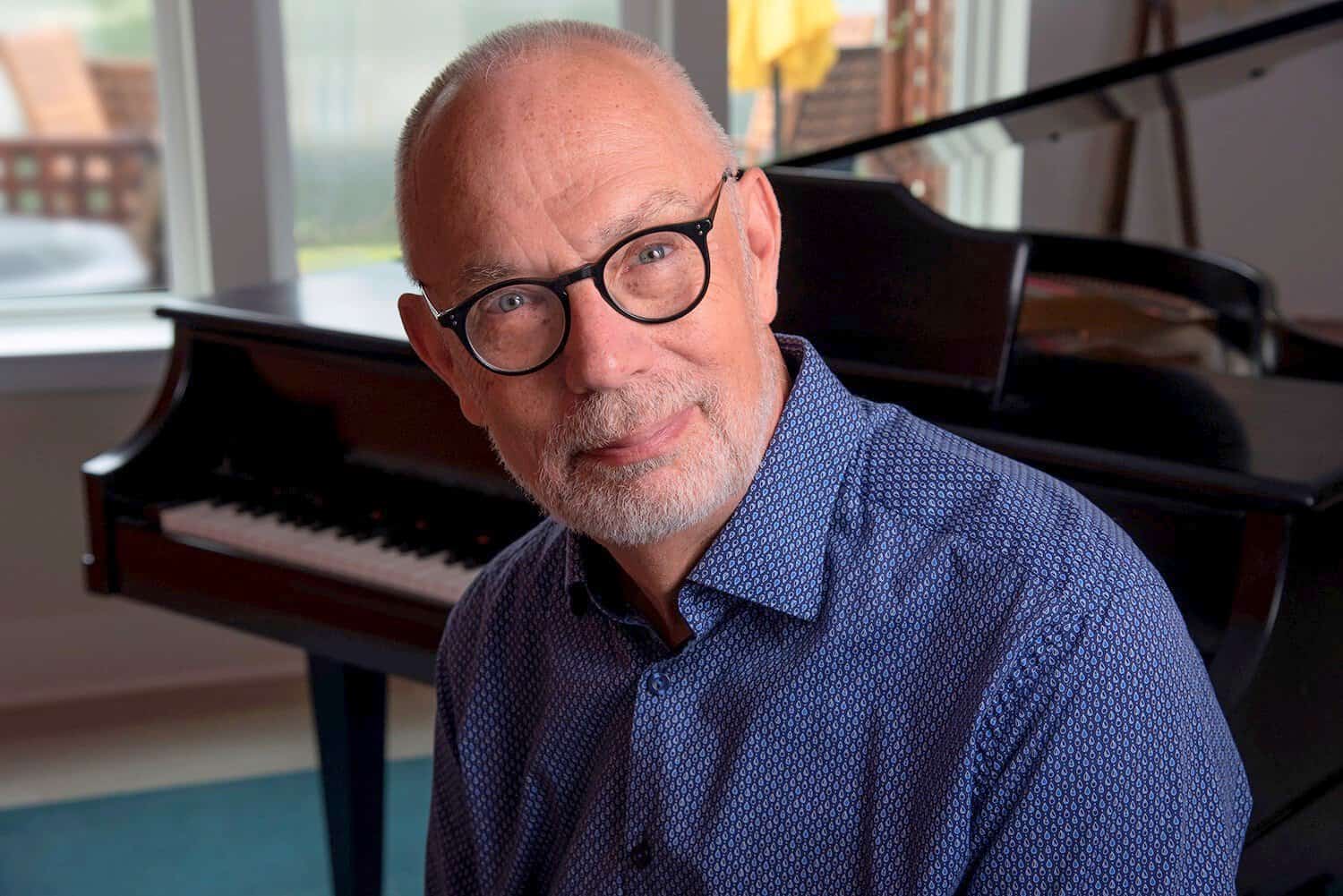

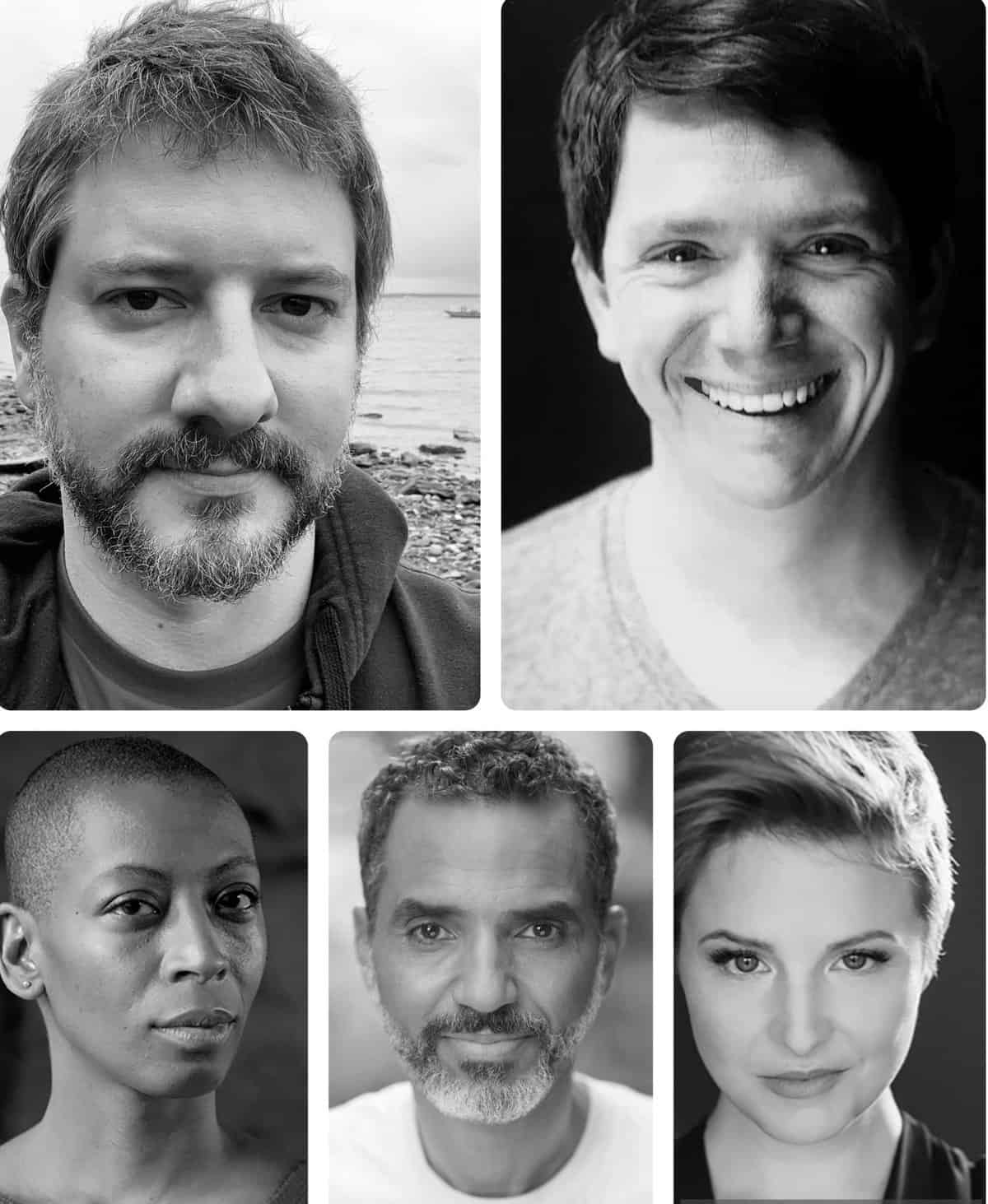

One of them came from the city’s health commissioner, Thomas Farley. The other three came from Alexis Roth, an assistant professor at Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health; Bonnie Milas, a professor of clinical anesthesiology and critical care at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine; and Bill Kinkle, a registered nurse and co-host of the Health Professionals in Recovery podcast. All four testified against the bill.

The chasm between the four medical professionals and some residents at the meeting is at some level representative of the bigger picture. Despite observational opposition from Philadelphia residents, the medical community seems to be generally in favor of safe injection sites. Most studies seem to show they save lives, promote safer injection conditions, reduce overdoses, increase access to health services and were associated with less outdoor drug use.

The evidence doesn’t appear to show that these sites have any negative impacts on crime or drug use. For these reasons, safe injection sites have been endorsed – as Dr. Farley pointed out in the hearing – by the American Medical Association and the Pennsylvania Medical Society.

But residents still aren’t having it.

“Why would we want to be the first to experiment on this?” asked Packer Park Civic Association president Barbara Capozzi in her testimony. “It makes no sense whatsoever. I’m full of compassion for [people suffering from drug addiction], but I’m more full of compassion for my residents and all the residents symbolized by these civic associations.”

Capozzi’s sentiment was echoed in the testimony of South Philly resident Anthony Giordano, who represented a community group called Stand Up South Philly and Take Our Streets Back.

“Safe injection sites are not safe,” he said. “Allowing people to consume illegal drugs of unknown composition in a so-called medical facility is beyond my comprehension. How is this safe? Helping people further harm themselves under the guise of a legitimate medical intervention just doesn’t make any sense.”

The testimony of Milas, the Penn anesthesiology professor, showed a perceived frustration within the medical community for its relative lack of influence over policy, at least when contrasted with that of residents’.

“It amazes me that we’re sitting here talking about making a medical decision and we’re listening to public opinion,” she said. “We need to make this based on information like Dr. Farley suggested: medical consensus, meta-analyses and a medical opinion.”

Milas was unique among the four medical professionals because the opioid crisis had affected her a bit more personally. She had two sons die of opioid overdoses – one was 27 and other 31, she said.

“At the 100 legal supervised injection sites worldwide, there are no recorded deaths,” she testified. “Had my sons overdosed at a Safehouse-type facility, they would have had a 100 percent chance of survival.”

Roth piled on.

“The scientific evidence from peer-reviewed journals on these sites is clear,” she testified. “They reduce overdose mortality rates, HIV, environmental hepatitis risk, they improve access to health and social services, they help reduce substance use and help people enroll in treatment. Furthermore, they’ve helped improve community health and safety. In neighborhoods where a [safe injection site] exists, there are actually reductions in public injection and improperly discarded syringes, reductions in drug-related crime, and the demand for ambulance services for opioid-related overdoses goes down.”

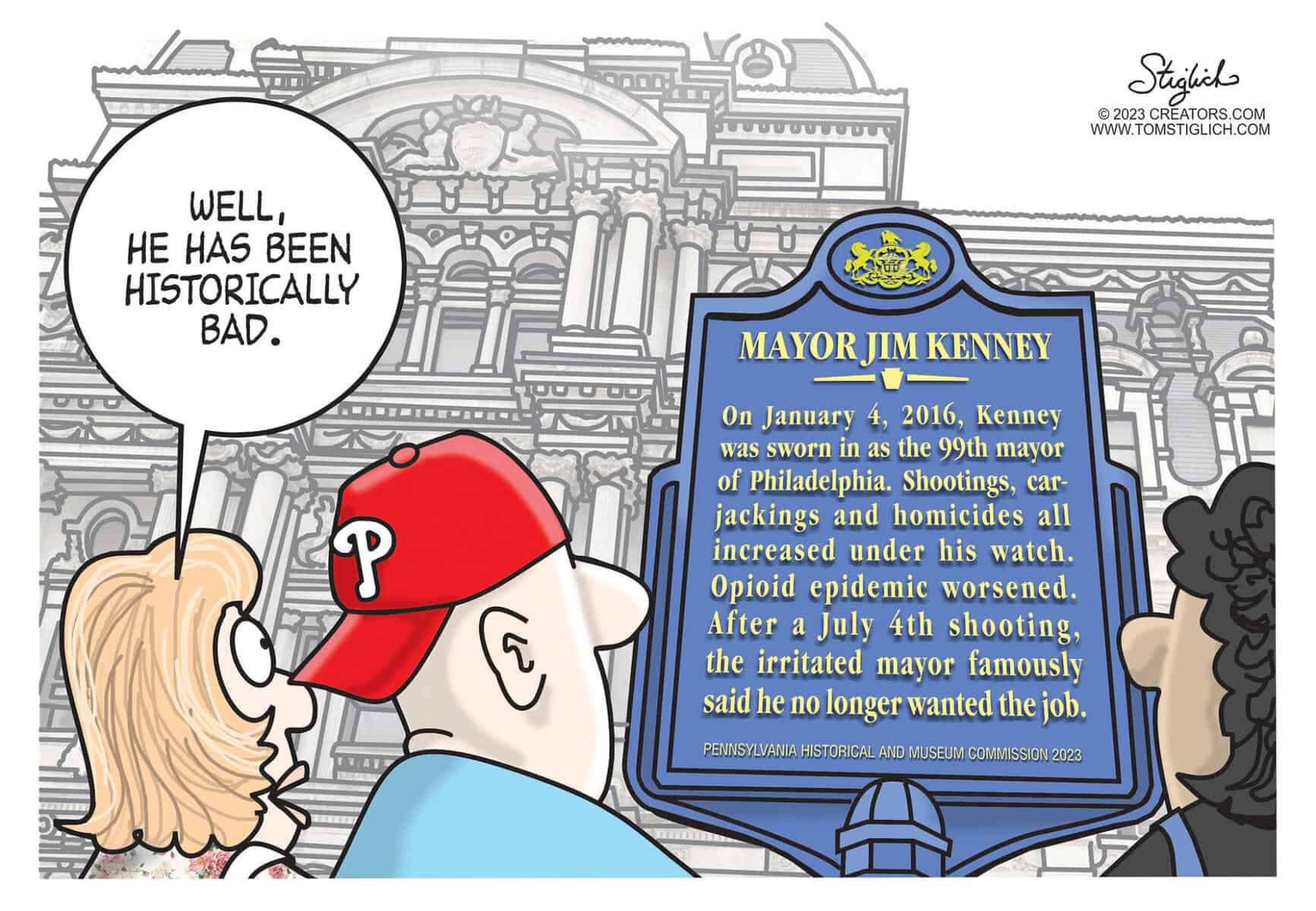

Wanting to show that there’s evidence against safe injection sites as well, Oh presented evidence of his own. A “very credible” study, he said, released this month by the government of Alberta showed evidence against the medical facilities.

“People who are for safe injection sites will not like the results of this study,” he told Farley during his testimony. “It is a very impactful, very credible study done in Alberta looking at all of the safe injection sites there, raising a lot of issues and providing a lot of information that actually refutes a lot of what you said about earlier studies.”

The study found, among other things, that 56 percent of people surveyed thought that walking in their neighborhood after dark had become less safe since a safe injection site opened in their city.

This study, however, has actually had its credibility publicly called into question by numerous academics.

“I would say that the only conclusion that a reasonable and fair-minded reader should draw is that the report is a political document and not an objective or scientifically credible evaluation of supervised consumption sites,” Cameron Wild, a professor at the University of Alberta’s School of Public Health, told the Calgary Herald. “It’s really impossible in the end to tell whether the results that appear (in the report) were cherry-picked to justify certain conclusions, or whether the results really fairly represent the diverse views that were obtained.”

The same Calgary Herald report cited Jenny Godley, a professor who teaches at the University of Calgary’s Department of Sociology, who said the study’s data should be “taken with a grain of salt” and that it “wouldn’t pass my undergrad stats class.”

An op-ed by University of British Columbia law professor Benjamin Perrin called the study “dangerously biased” and “methodologically flawed.” He added that it “explicitly ignores over 100 peer-reviewed studies on the benefits of [safe injection sites].”

The Review asked Oh’s office if Oh still stood by the study in light of the criticism.

“The Alberta study is long awaited and highly credible,” Oh responded in an email sent by spokesman Tyler DeBusi. “It is backed by independent data and corroborated by eyewitness testimony and visible evidence. People can read it and decide for themselves.”

SPR asked residents why they don’t support safe injection sites despite the evidence presented by the health community. In an email to the Review, Capozzi, who wasn’t willing to talk over the phone, disagreed with the premise. She argued that the split wasn’t so much between residents and the medical community so much as it was among liberals and conservatives.

“[A]lmost by definition academics are quite liberal,” she said. “The divergent opinions are also the difference between people in the real world vs. people with a whole lot more ‘book smarts’ than street sense or common sense.”

She also argued that the results of various studies completed in Canada weren’t necessarily representative of Philadelphia’s relatively poor community.

“I have seen no evidence that this type of facility would work in Philadelphia, with its very poor population,” she said. “SIS is a concept that has never, ever been tried in the USA with its very poor, and very diverse urban populations. We are not Sweden, we are not Canada.”

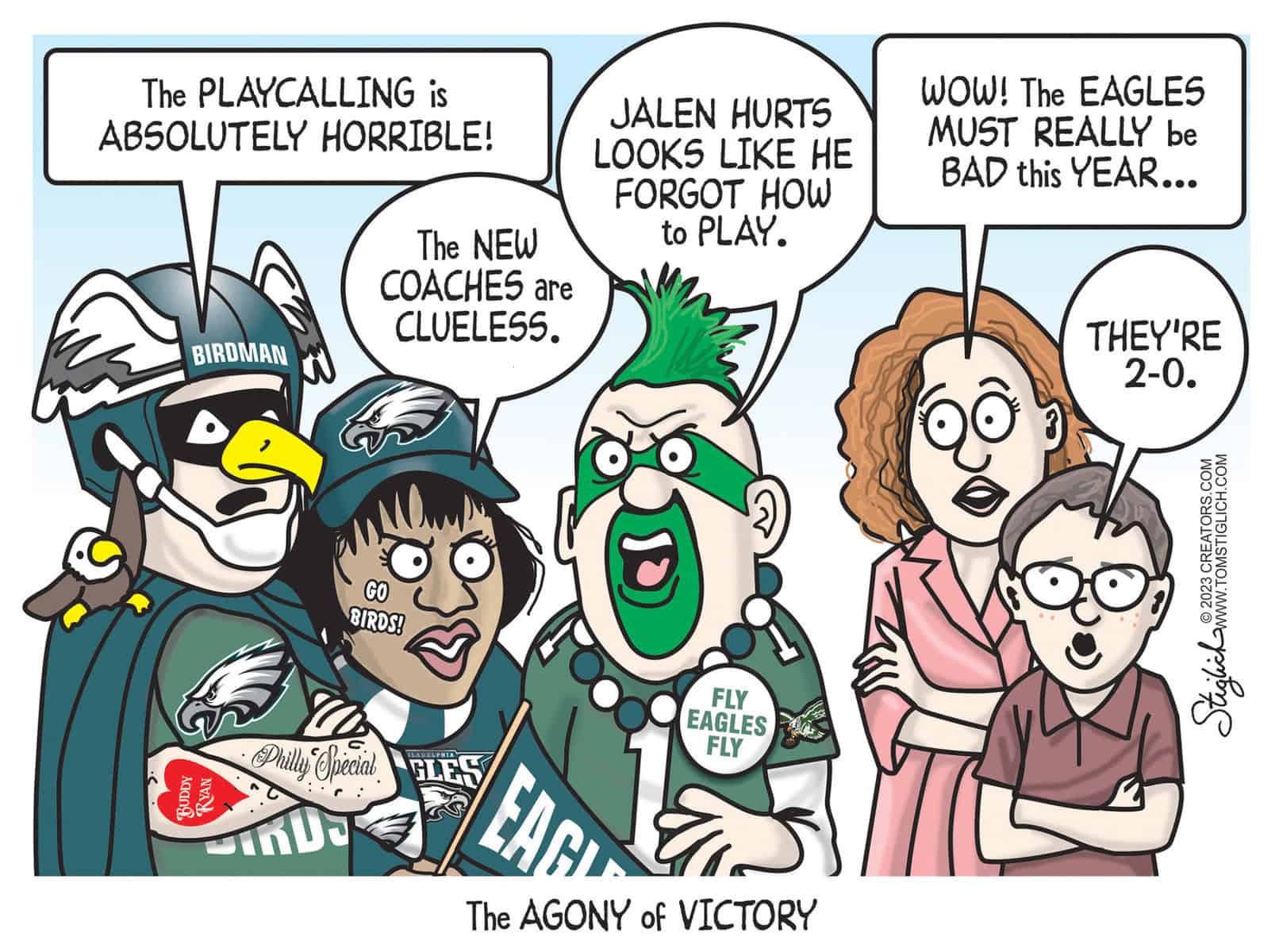

At an anti-safe injection site protest outside of Kensington’s McPherson Library on Saturday, Philadelphia resident Richie Antinupo expressed similar concerns.

“Show me the studies and where they [were conducted].” he said.

The Review informed him that they mostly had been conducted in Canada.

“OK, well that ain’t here, is it?” he replied. “Just because it works somewhere else does not mean it’ll work here, or vice versa.”

Antinupo was also afraid that safe injection sites were a slippery slope to things like opioid “vending machines,” which has, in fact, begun to happen in Vancouver.

Capozzi said that she couldn’t see herself changing her mind, in part because she thinks safe injection sites “condone” and “enable” drug use.

“I cannot imagine what would convince me that enabling addicts and making it easier for them would actually help them in the long run,” she wrote. “Condoning drug use and making it easier, no matter what form it takes, is wrong, wrong, wrong.”

During Monday’s hearing, only Councilmember Helen Gym, who voted against advancing the bill, asked for more details on the science.

“I don’t think any of us on Council have a medical degree,” she acknowledged to Farley. “From a medical perspective, why does the AMA support these facilities?”

“Because they reviewed the full scientific literature and looked into what they provide,” responded Farley. “And they acknowledge that opioid overdoses is a common problem, that they reduce overdose deaths and that they potentially serve as a side to treatment.”

The legislation proposed by Oh initially required 90 percent of a community’s approval within 1 mile of a proposed safe injection site before it could open and operate, a threshold many think can’t possibly be met. However, at the end of the meeting, the bill was amended to lower the thresholds from 90 percent to 80 percent and from 1 mile to a half-mile. It subsequently passed by a vote of four to two, advancing it out of committee. Councilmembers Cindy Bass, Isaiah Thomas, David Oh and Bobby Henon voted in favor, while Gym and Kendra Brooks voted against.