It was two years of work, but a lifetime in the making.

It was two years of work, but a lifetime in the making.

Katherine Antarikso was 10 when her family permanently left Indonesia in 1988. The transition wasn’t easy and not many people from her country were being accepted into the United States at that time, despite a continuous flow of European migrants crossing the border and starting new lives in America.

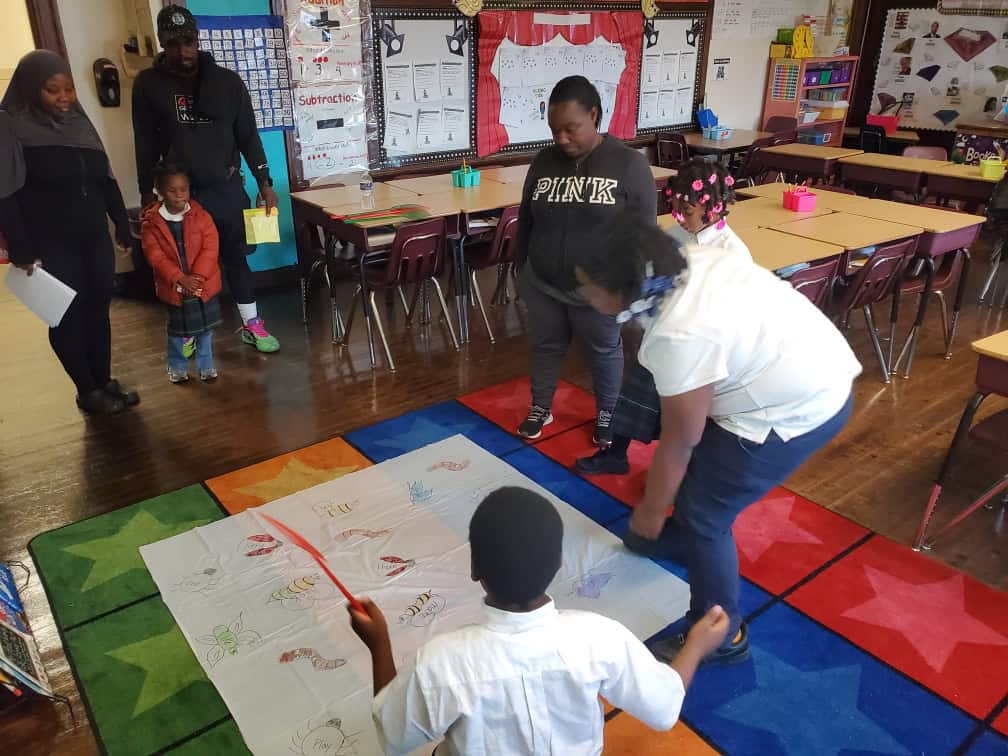

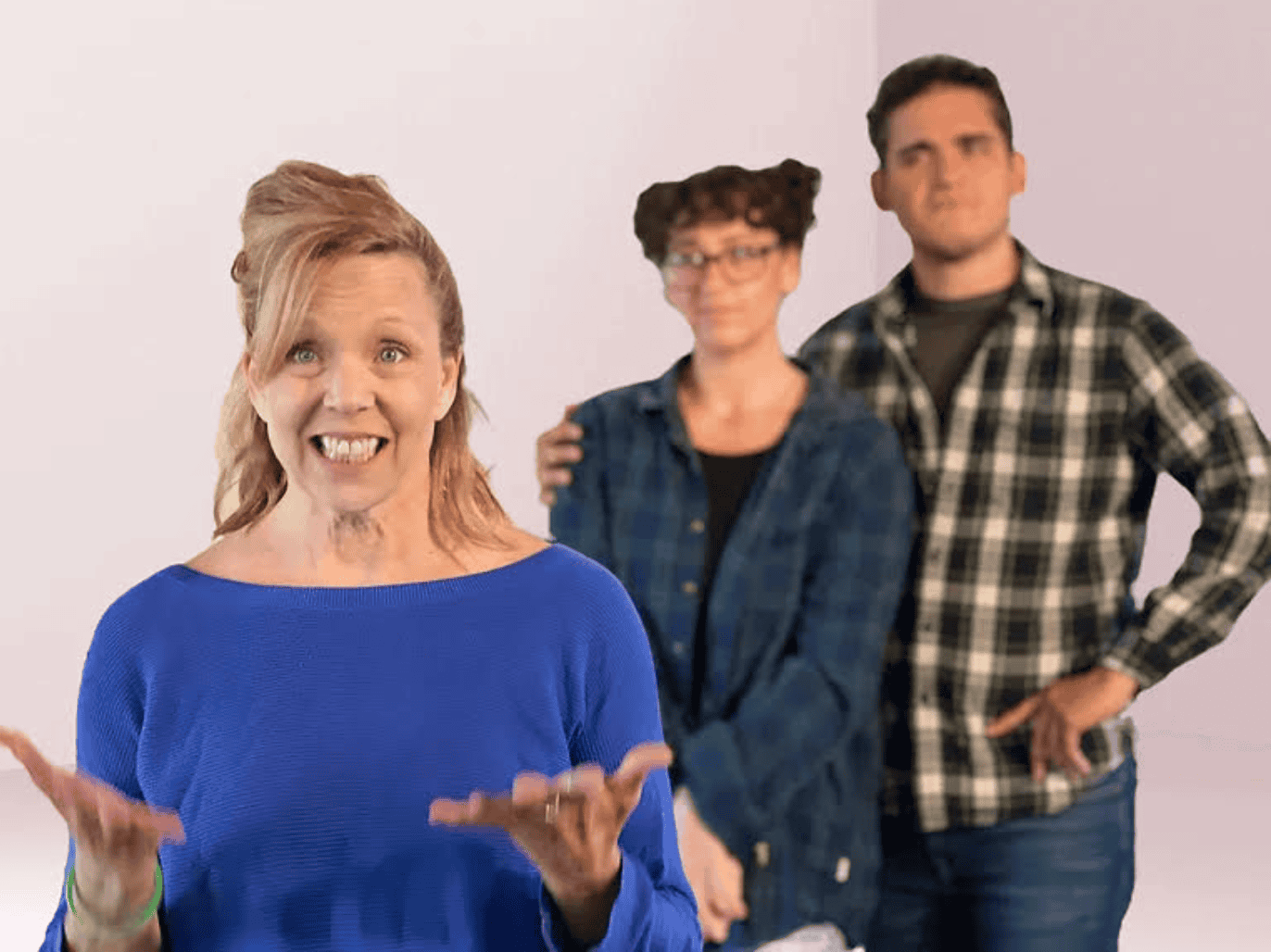

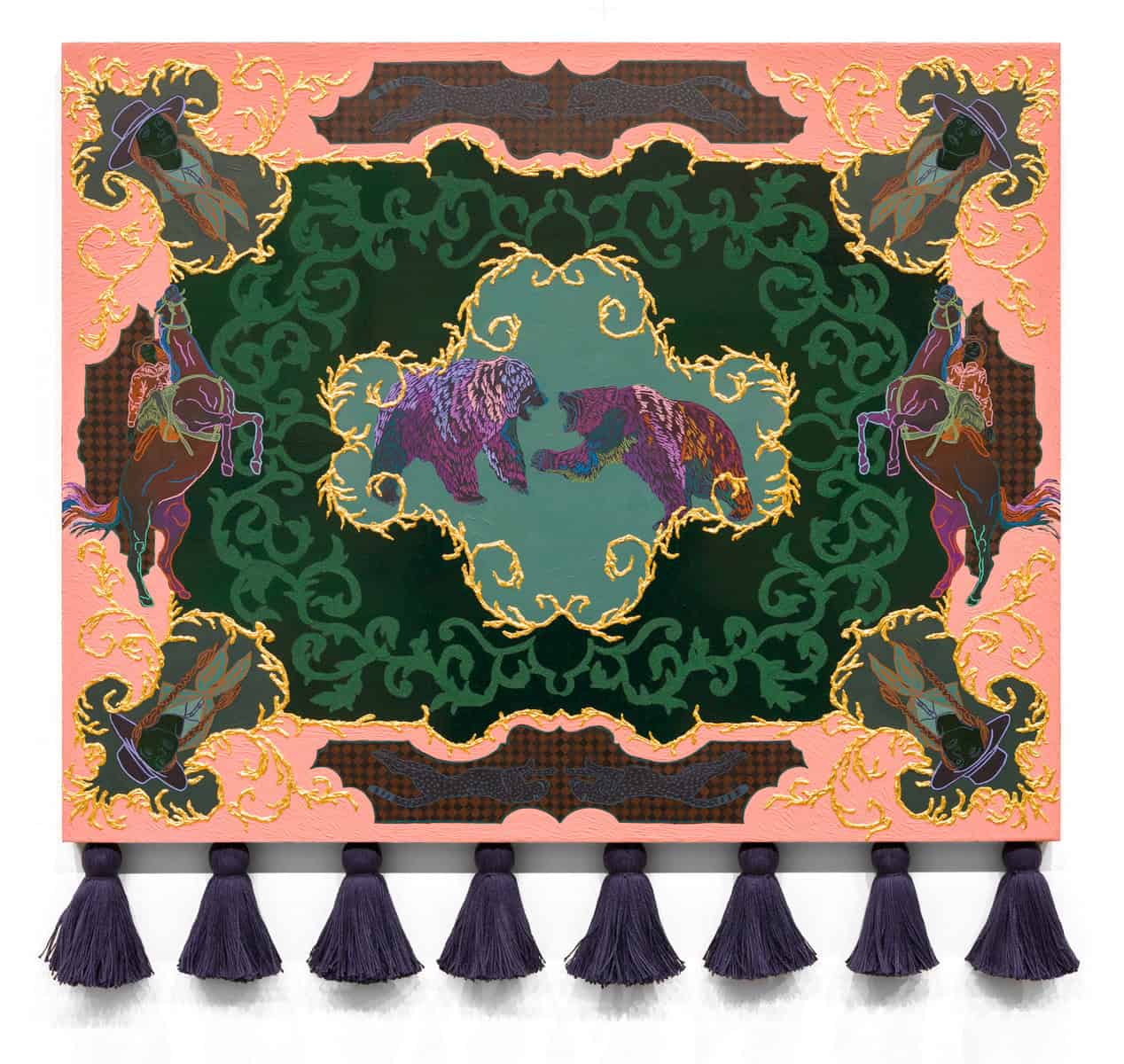

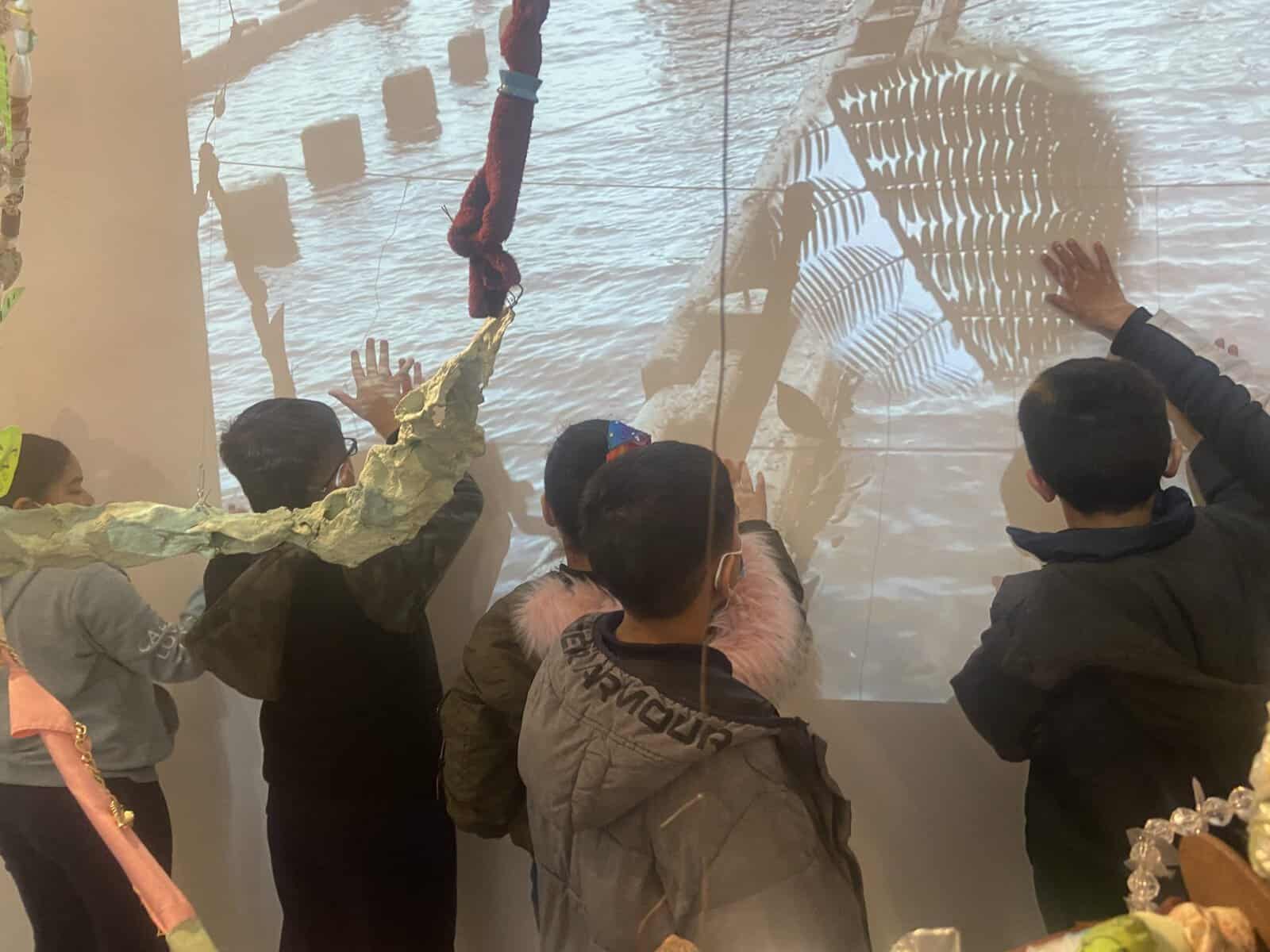

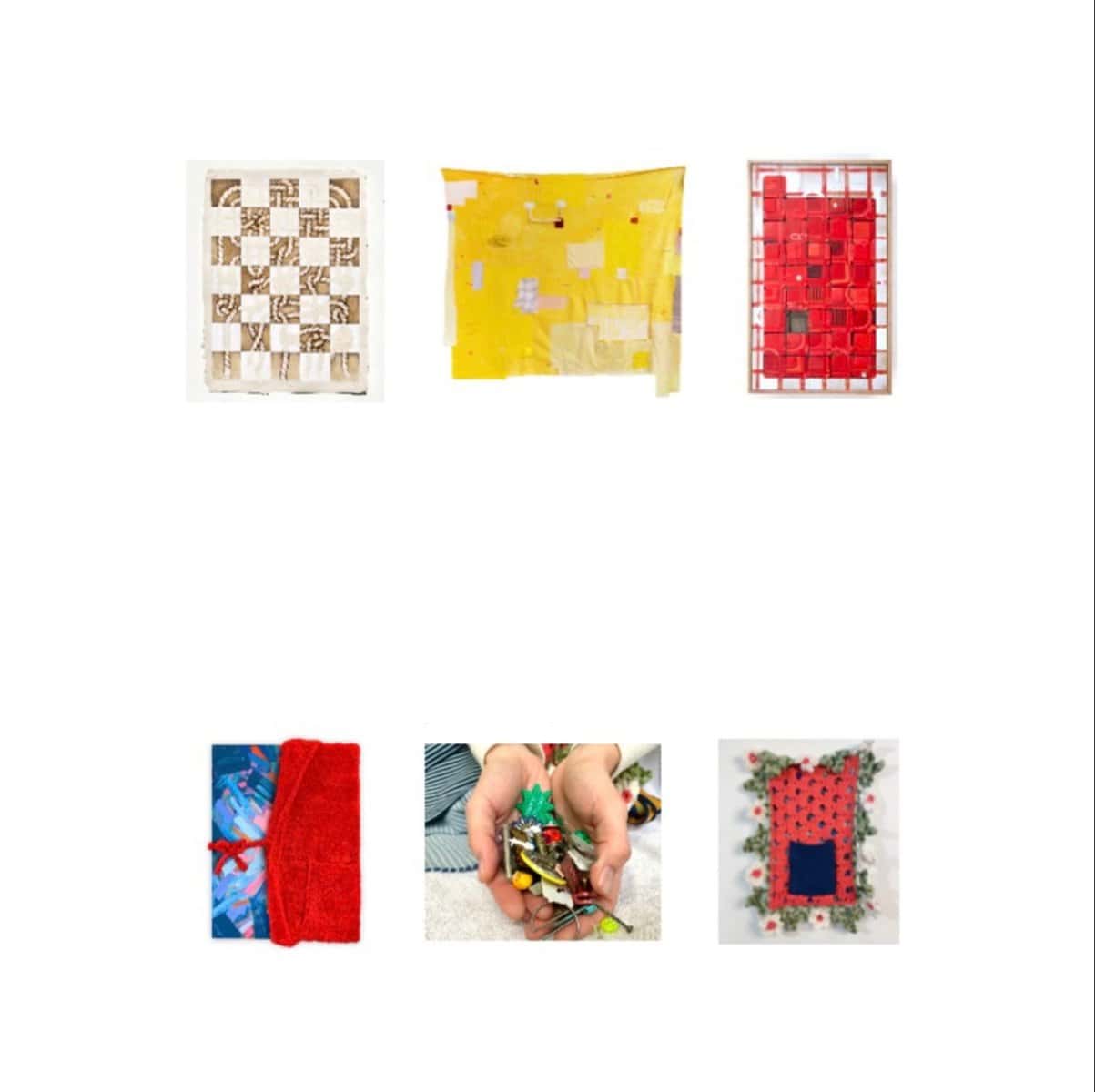

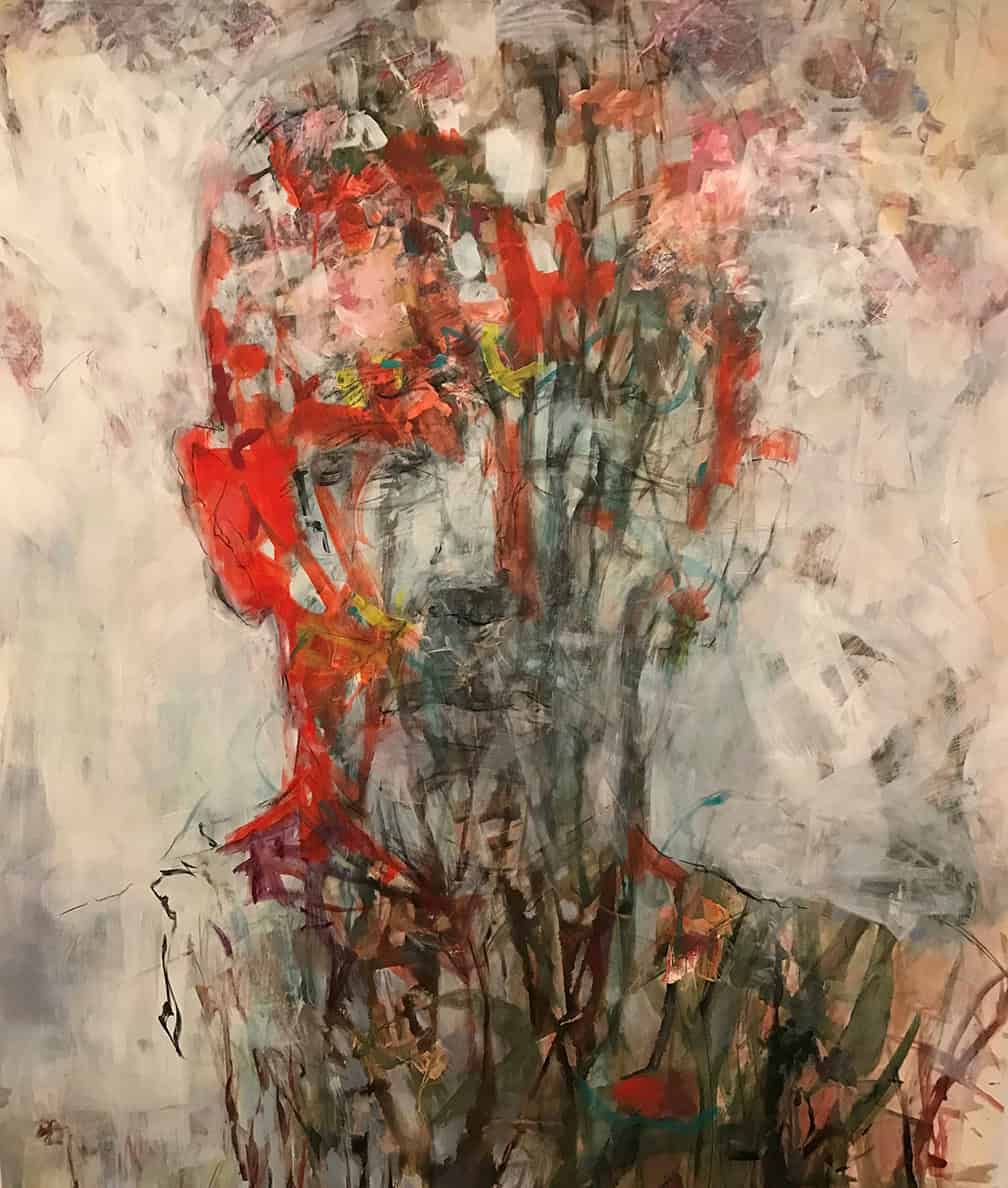

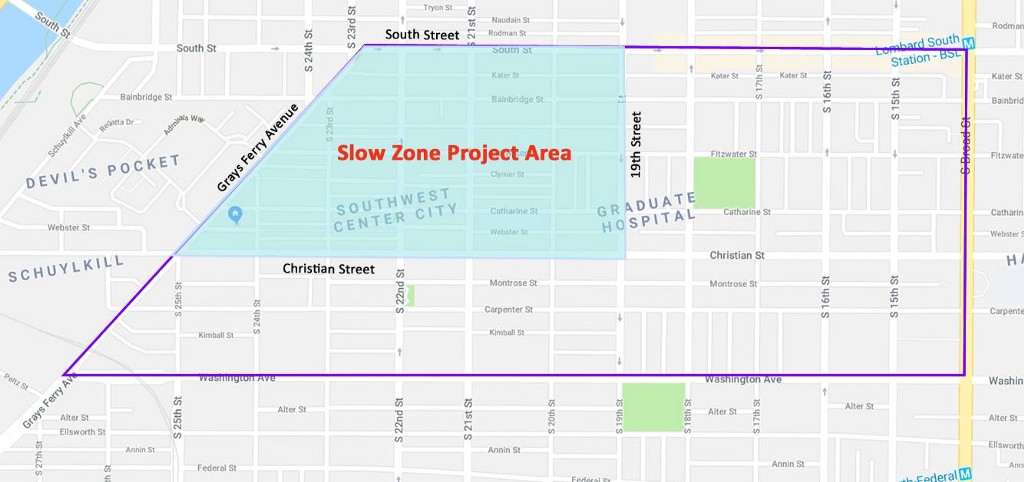

Those memories are still vivid for Antarikso, who now lives in the Graduate Hospital neighborhood of South Philadelphia. And she’s sharing her experiences through a project at both the Parkway Central and South Philadelphia Free Libraries called “Chronicling Resistance.”

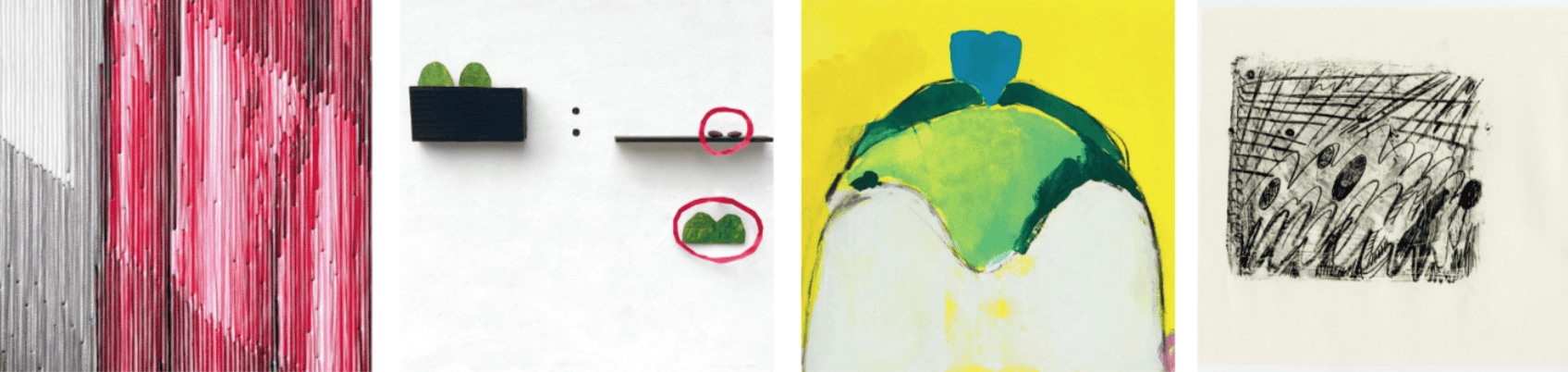

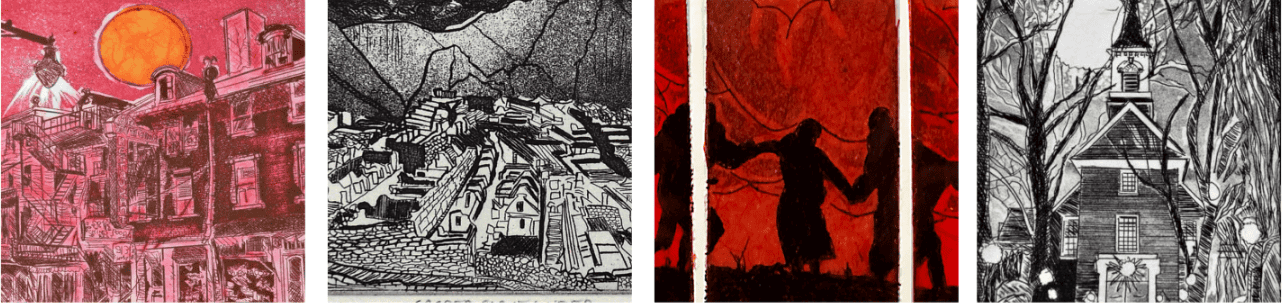

The exhibition features two fellowship curators showing separate projects under the theme, focusing on Southeast Asian resistance history in Philadelphia.

Antarikso was joined by fellow artist Lan Dinh in opening the exhibition in September. It will run through Jan. 31 at both libraries.

“It sounded really interesting to me because it was a chance to research the library’s archives,” Antarikso said. “I had been interested in understanding how our history can inform us. I had been working with some immigrants rights groups and people in the Indonesian community to fight for our rights for immigrants here in South Philadelphia. The call was for activist curators, so it seemed like an amazing opportunity. I applied and I was honored to be a part of this project.”

Antarikso was born in Indonesia’s capital city of Jakarta on the Island of Java and followed her father’s dreams of education as he attended Penn State University, a school she would later attend as well. After college she moved to Philadelphia, where her sister already resided. An architect by trade, Antarikso was interested in the city’s Chinatown section and saw similarities in community structure.

“I wanted to research the history of Chinatown in Philadelphia and how people create ethnic enclaves as immigrants to create a sense where they can create a community,” she said. “I wanted to know what we could learn from that as the Indonesian community. We feel a sense of belonging in Chinatown because it’s a little bit more familiar to us. It was interesting to me that they created an enclave where they could be self-supportive and create businesses.”

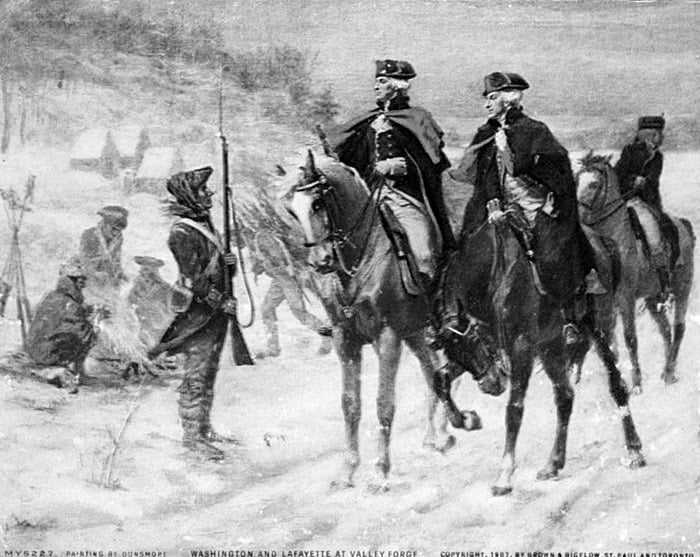

She also realized that many Indonesian immigrants like herself didn’t learn much about her country’s history while living in America, despite Indonesia being the fourth-largest country in the world by population. She had never heard of the Bandung Conference, which was held in Indonesia in 1955 and was an important meeting of 29 governments of Asia and Africa that discussed peace and the role of the Third World in the Cold War, economic development and decolonization. It was an important historical moment as leaders of developing countries banded together to avoid being forced to take sides in the Cold War.

“I never learned about it growing up at all until I went to Indonesia in 2011 and I was interested in the building because I was an architect,” Antarikso said. “I didn’t realize the history and what a momentous occasion that was seeing all these different countries coming together to move forward and help each other. I wanted to learn from history and see what acts of resistance were successful and try to inform us on how we could resist some of the unjust laws we are facing right now.”

Antarikso was inspired to show her findings to help educate others about Indonesian history. Her display of research just beyond the library’s main entrance recognizes the narrative of many immigrant communities, from displacement following war and political upheaval to establishing and growing community through mutual aid and holding onto cultural traditions.

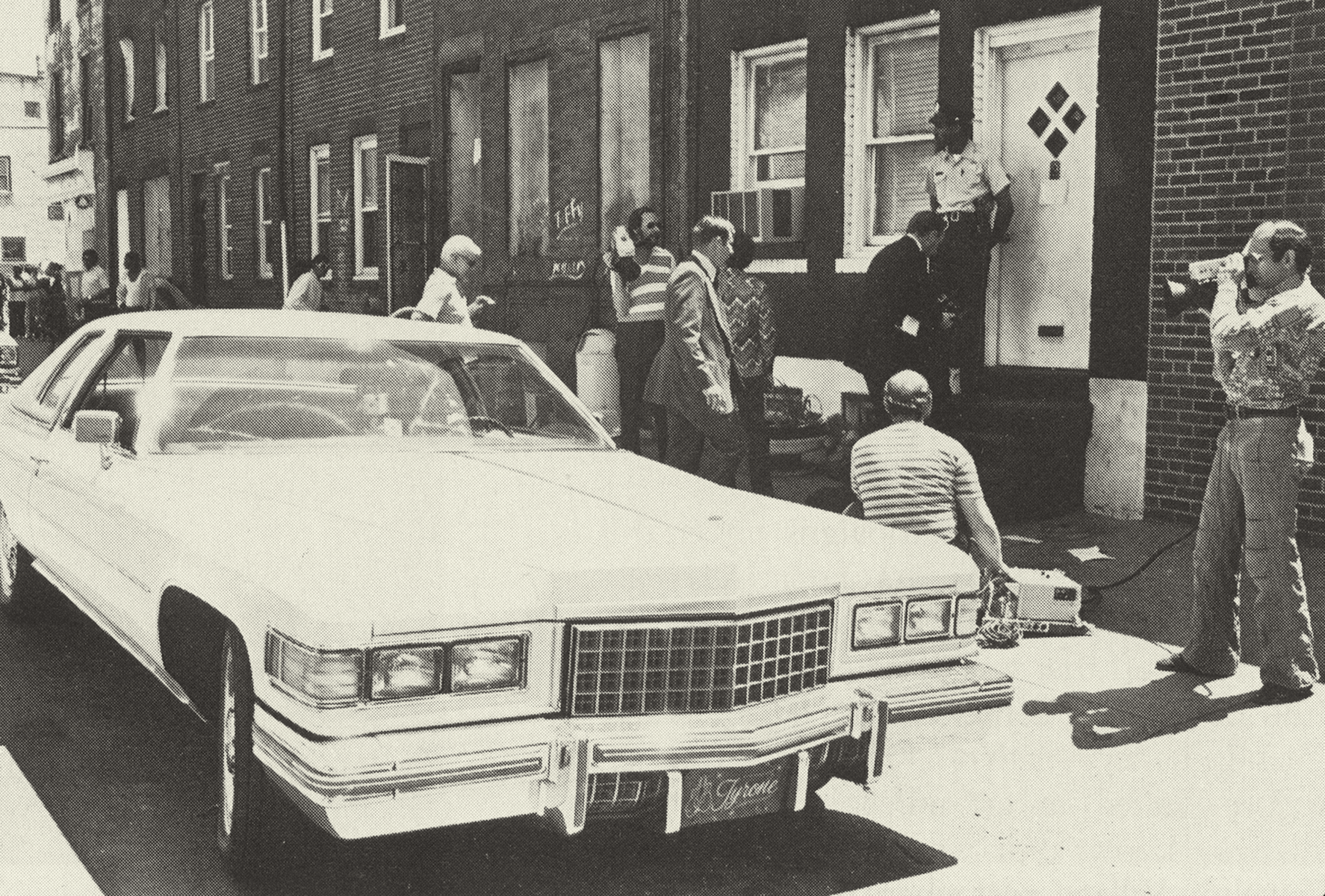

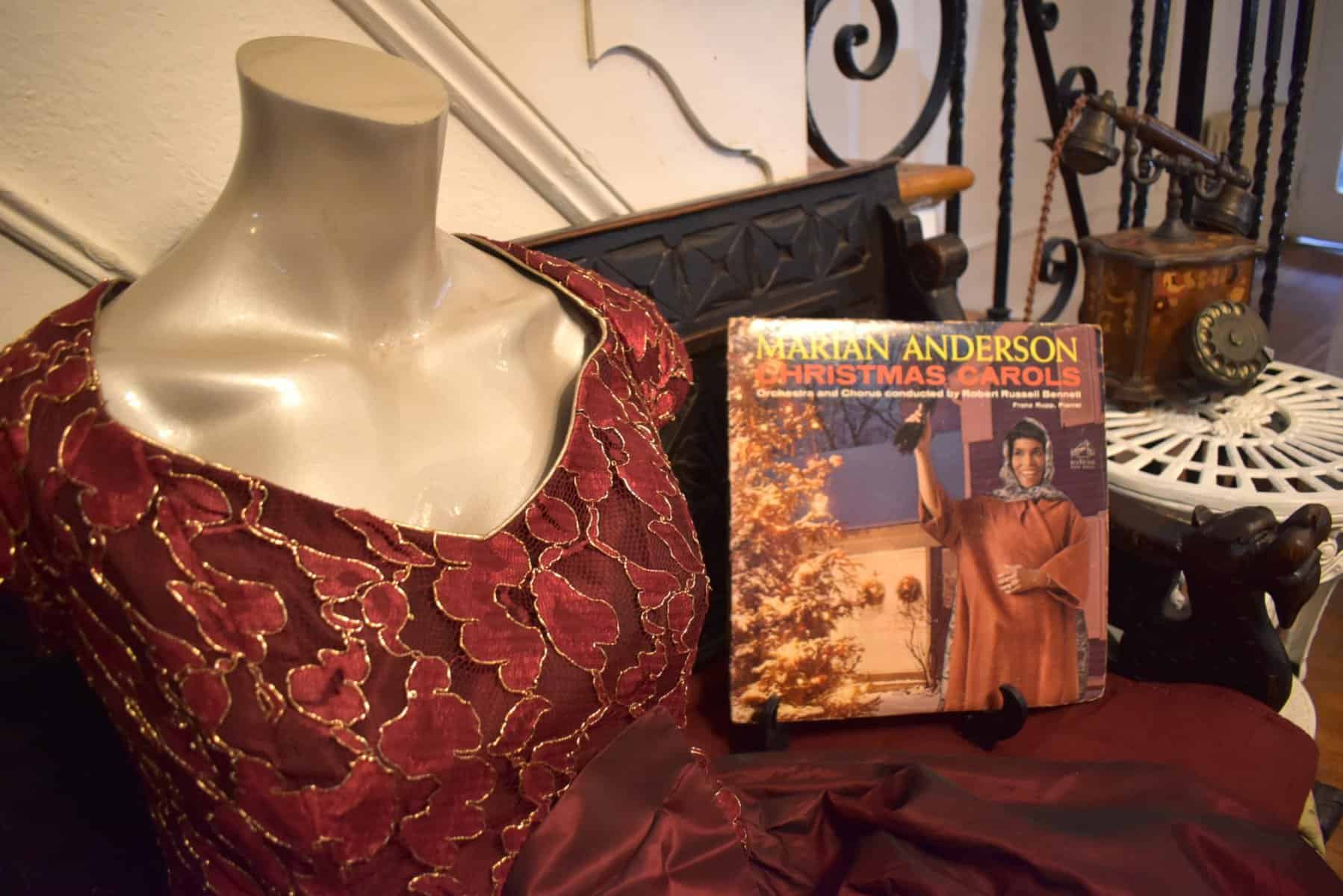

The physical work of the project began two years ago, but the ideas have been brewing much longer. The exhibit includes archived articles, maps, immigration statistics, photos, poetry and even her father’s immigration papers from 1976 when he first came to the U.S. to study.

The goal was to preserve and illuminate centuries of systematically excluded history while highlighting stories from current and historical movements resisting oppression and marginalization.

The goal was to preserve and illuminate centuries of systematically excluded history while highlighting stories from current and historical movements resisting oppression and marginalization.

“I’m very proud of this exhibit,” Antarikso said. “I think it’s a once-in-a-lifetime chance. I’m very glad there was an opportunity for this self-directed research. They gave us a lot of independence for which items were significant to our community.”

Although they are two different projects, Antarikso conferred with Dinh often during the course of the projects as the two gathered information.

“Lan and I talked a lot,” Antarikso said. “We were the two Southeast Asian fellows and we wanted to bring some of the exhibit here because this is where the biggest Southeast Asian community is. During the process, we talked about our progress and what we are seeing and what common themes we had like responses to colonization. It was really amazing when we got together and got to talk about what we were finding in the archives and even the frustrations of not finding anything about our people.”

What she did find was an Indonesian community in Philadelphia and many others that are eager to learn about the history of her country.

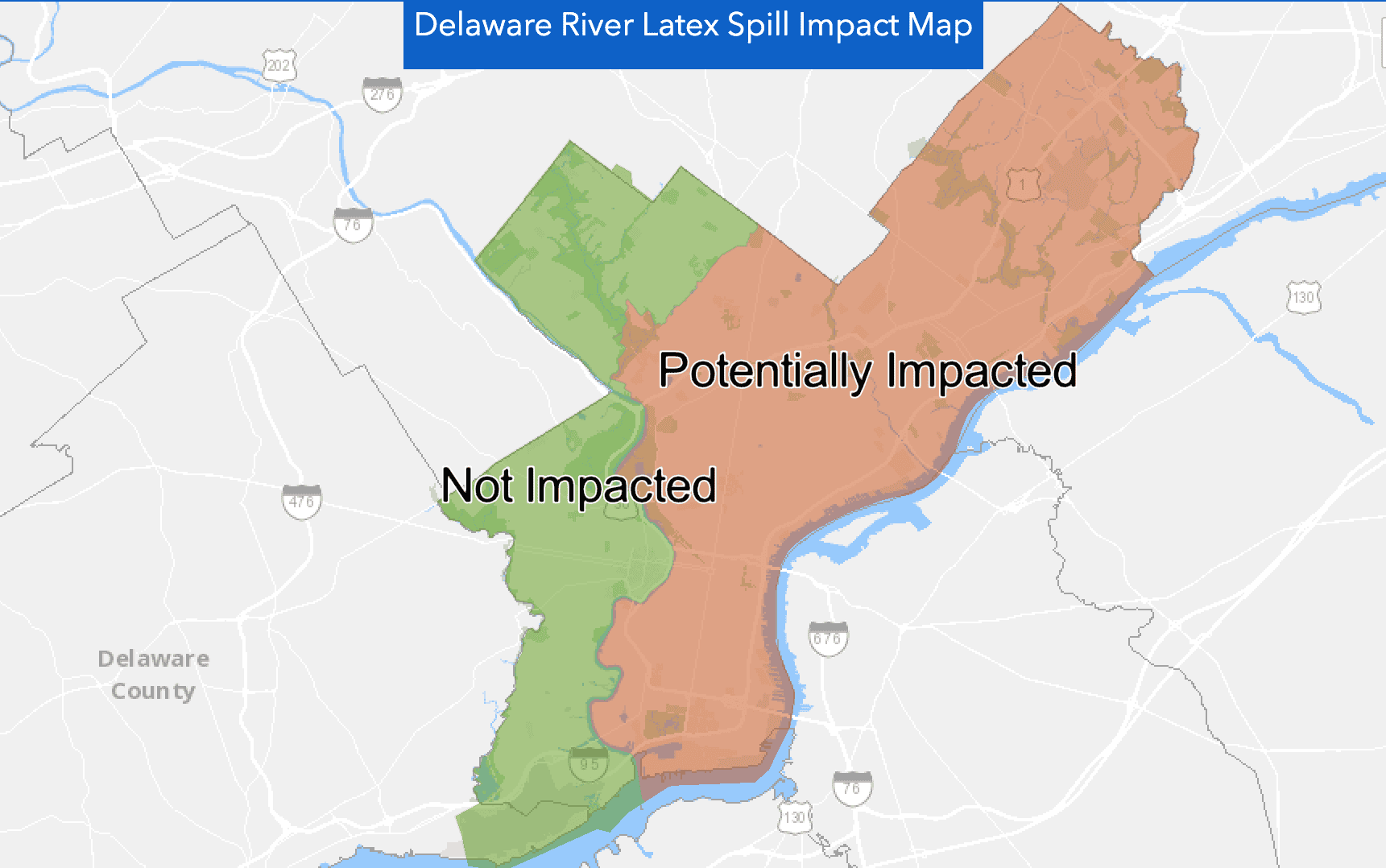

“A lot of the Indonesian community is in South Philadelphia,” she said “I’m now part of an Indonesian dance group and we now have a little community center here. So I wanted to bring the exhibit from the central library to South Philadelphia so the Southeast Asian community can see themselves reflected here and read the stories. There’s really not a lot about us so I wanted to bring these stories up and put us on the map.”