Marian Anderson’s voice helped change the world. And it’s still needed.

Marian Anderson’s voice helped change the world. And it’s still needed.

The famous opera singer was one of the most iconic and influential figures in both local and American history, breaking the color barrier as the first African American to perform at the Metropolitan Opera and on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. She toured the world with her music and serenaded U.S. presidents at their inaugurations.

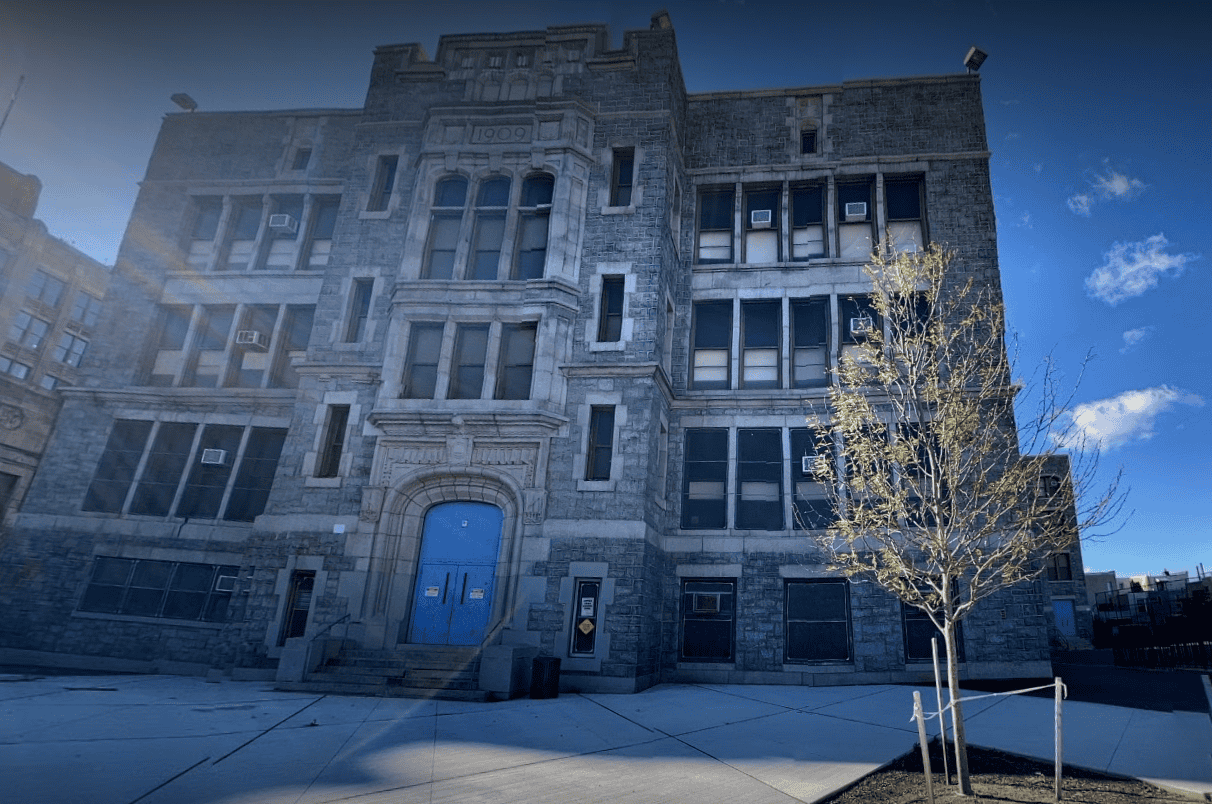

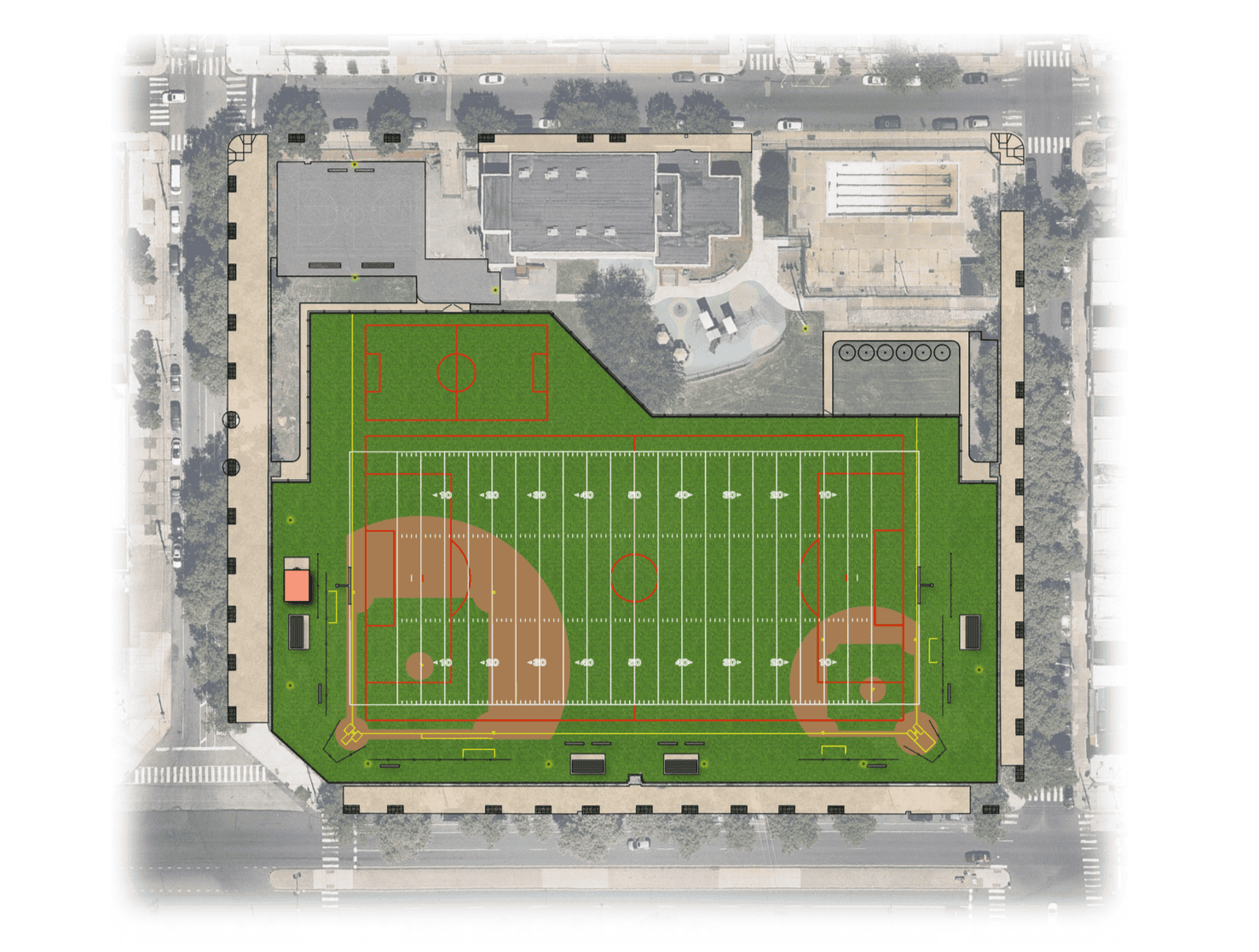

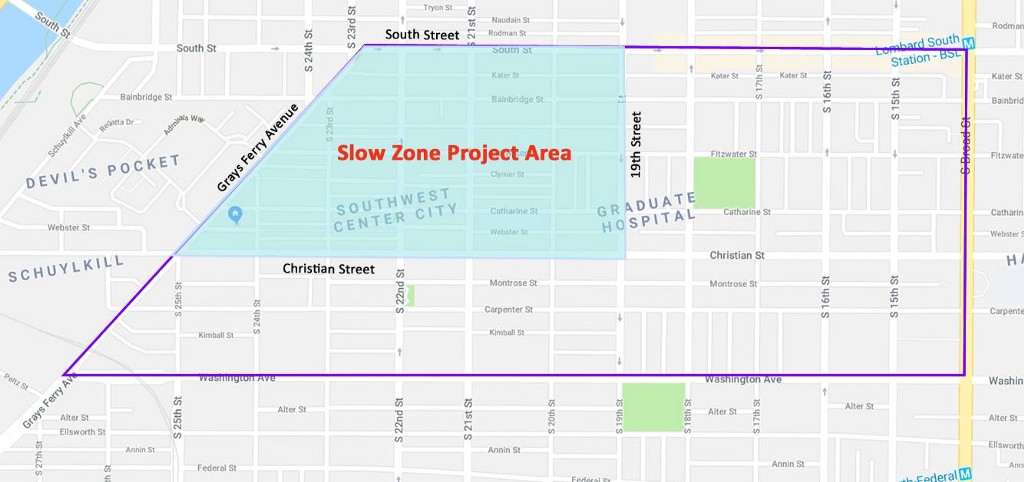

The Marian Anderson House at 762 S. Martin St. in the Graduate Hospital neighborhood honors the late singer and serves as a museum and a home to the Marian Anderson Historical Society. Known as a South Philadelphia treasure, Anderson’s house was placed on the National Register of Historical Places in 2011.

To many people, it means so much more.

“It was Marian’s home,” said Jillian Patricia Pirtle, CEO of the Marian Anderson Museum and Historical Society. “All of the life and stories and treasures it has in it are such a blessing. It’s a legacy both historically and culturally.”

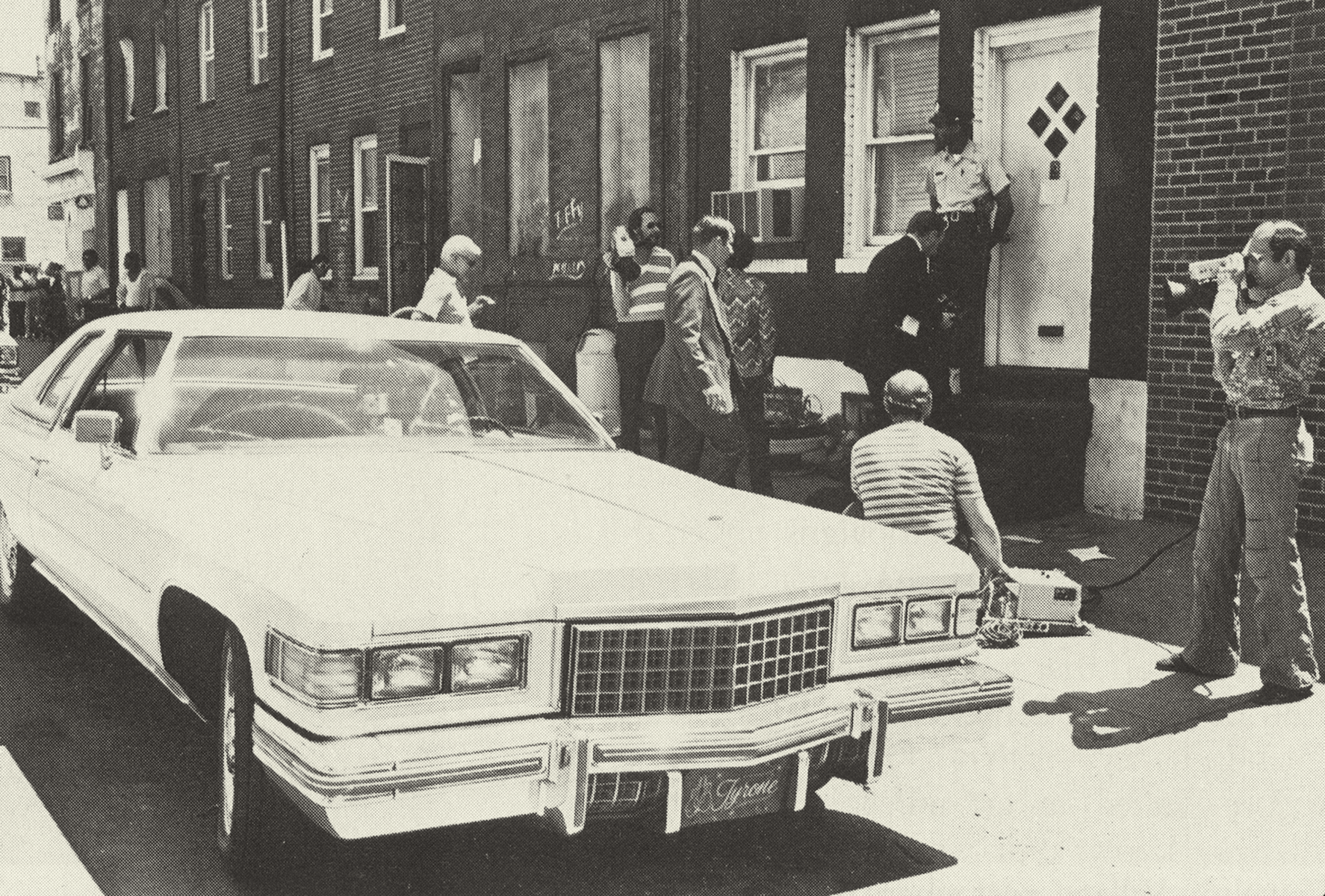

Anderson purchased the row home in 1924, a year before she performed with the New York Philharmonic. She transformed the basement of her house into an entertainment center because at the time, African Americans were often not welcomed to go out socially.

“In the 1920s, ‘30s and ‘40s, even as African Americans could perform at the Academy of Music and other theaters in Center City, people still couldn’t get open table seating because of the color of their skin,” Pirtle said. “So Marian converted the lower level into a second dining area and they had a lot of impromptu performances here.”

Popular musicians such as Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong were just some of the names known to have played at Anderson’s South Philly residence.

“So many people were in and out of here,” Pirtle said. “We breathe their rarefied air. It’s really something.”

And now that space is endangered.

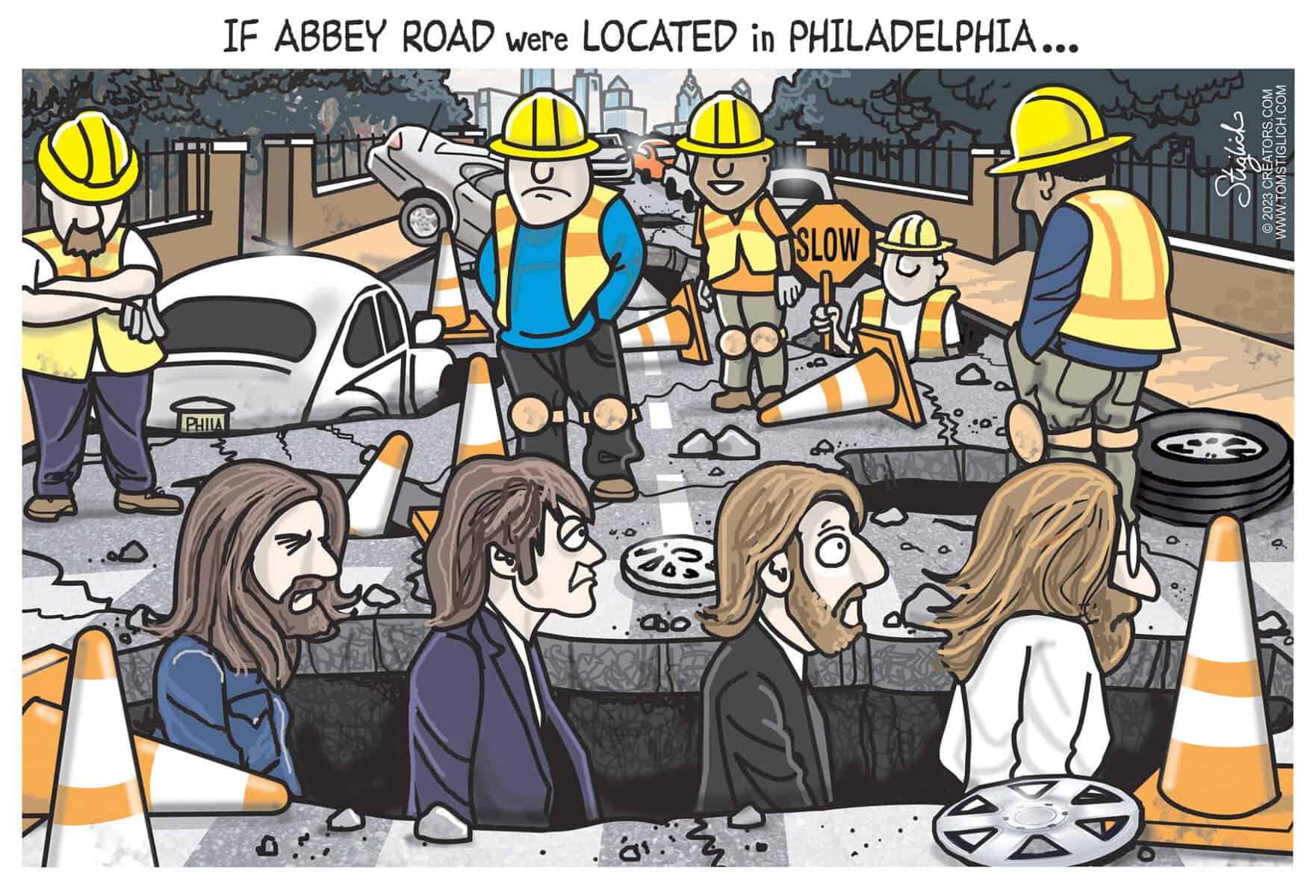

The Marian Anderson Historical Society has met its match in financial troubles in 2020. First, COVID-19 forced the museum to close in March, eliminating admission fees that pay the bills to keep it running. A few weeks ago, several pipes burst in the house, flooding the 1857 establishment and causing severe damage.

Since the house was closed to the public because of the pandemic, Pirtle said the building was vacant and no one knew of the severity of the situation until several days later, as water drenched the home. About three and a half feet of water was found in the basement, and several irreplaceable artifacts were damaged.

The cost to fix the pipes and restore the floor are calculated to exceed $5,000. The Historical Society was already facing a shortfall of about $12,000 due to the inactivity at the museum, placing it in a dire situation. A GoFundMe was created to raise funds, and supporters have raised more than $3,000, but the museum still has an enormous mountain to climb.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Pirtle said. “There are so many reasons for us to cry right now.”

Surprisingly, the Marian Anderson House receives virtually no help through grants or historical preservation funds despite applying for them annually. It is forced to rely heavily on admission and private donations.

“We fill out grants every year,” Pirtle said. “But we really don’t get any help that way. We have a couple of seniors that are supporters but other than that, we rely on foot traffic through the tours and those who buy tickets to our concert season.”

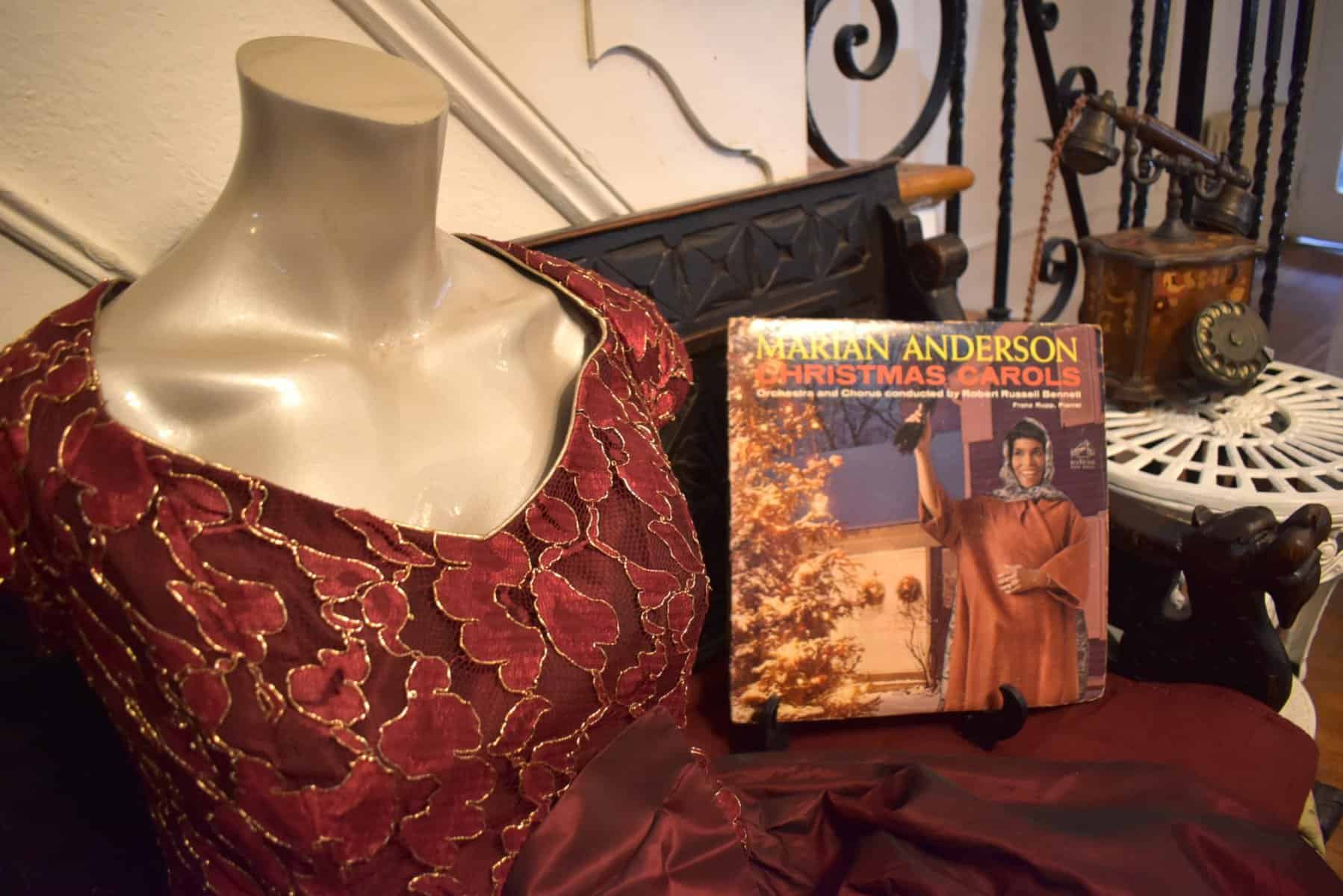

The house is extremely well kept, and the society provides new exhibits every year, giving annual visitors a brand new experience each time they arrive.

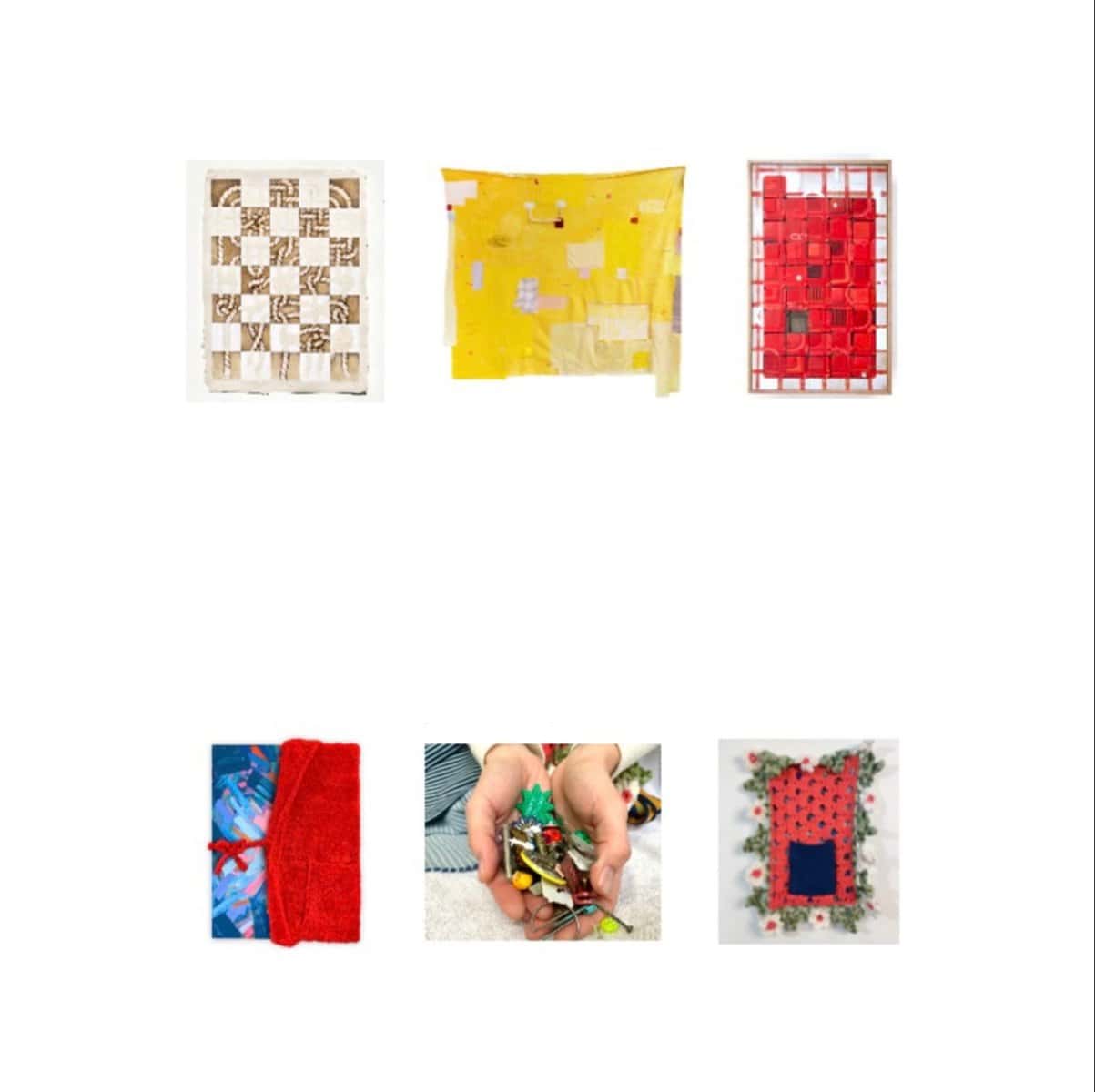

Last year, the museum showcased three floors of memorabilia, featuring never-before-seen gowns and costumes once worn by Anderson, along with 103 of her live recordings with Recording Artist Company.

This year’s exhibit opened in February, focused on Anderson and her relationships with other impactful women who helped shape the 20th century.

“We never have the same exhibit,” Pirtle said. “It’s always changing every year. We go into the storage facility and bring out new pieces that people haven’t seen. We do whatever we can to raise the attention and the awareness and visibility. But it seems not to resonate and that’s sad because Marian is so much to so many people in Philadelphia, across the nation and around the world. Sometimes, I get to the point when I’m asking myself when are people going to care about Marian.”

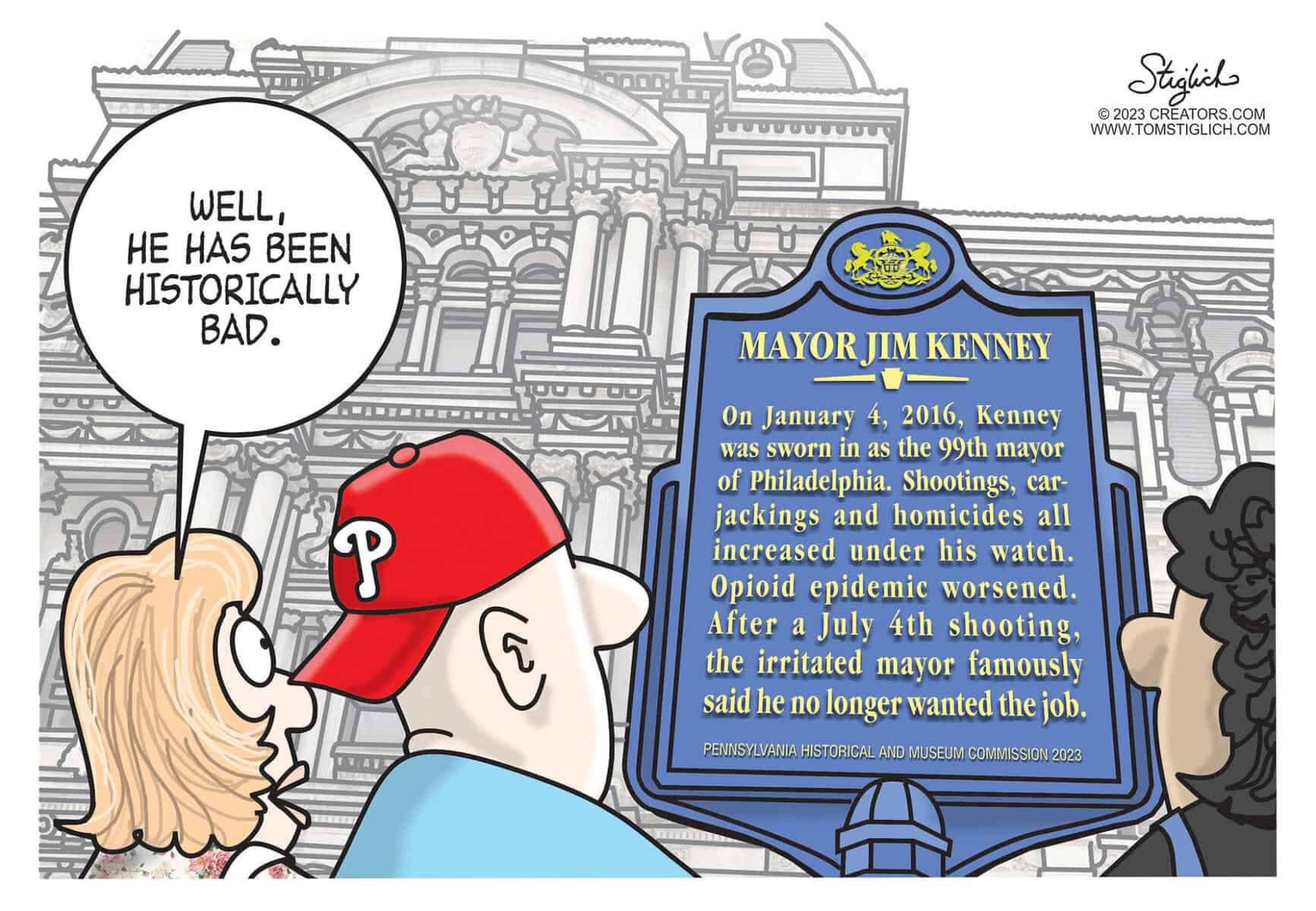

Pirtle said Anderson’s hometown of Philadelphia has perhaps taken this local treasure for granted.

“A lot of our attendance is from tour guests from out of town because, believe it or not, we don’t get any support from the city,” she said.

The Historical Society is still fighting. Although the pandemic has made things challenging, it will still present “Sacred Art Songs in Concert” on Sept. 5 at 2 p.m.— a livestream concert performance by the National Marian Anderson Scholar Artists. Donations will be accepted through the museum’s website at marianandersonhistoricalsociety.weebly.com.

Pirtle aims to keep Anderson’s memory thriving, much like society founder and multifaceted concert pianist Blanche Burton-Lyles did for more than two decades before she passed away in November 2018. Burton-Lyles bought the house on South Martin Street in 1997.

“One of the wonderful things about Marian was she wanted to make sure that the music and the legacy and the performance were going to live on in the next generation,” said Pirtle, who has donated much of her performance money back to the society. “(Burton-Lyles) wanted to revive the scholar artist program that Marian started. We’ve stayed with the program, and I’m trying to keep the legacy alive but it’s very hard because we still have to pay bills. It’s sad and it’s a strain but I’m praying that somebody can help us.”

To Donate: https://www.gofundme.com/f/support-for-marian-anderson-historical-society