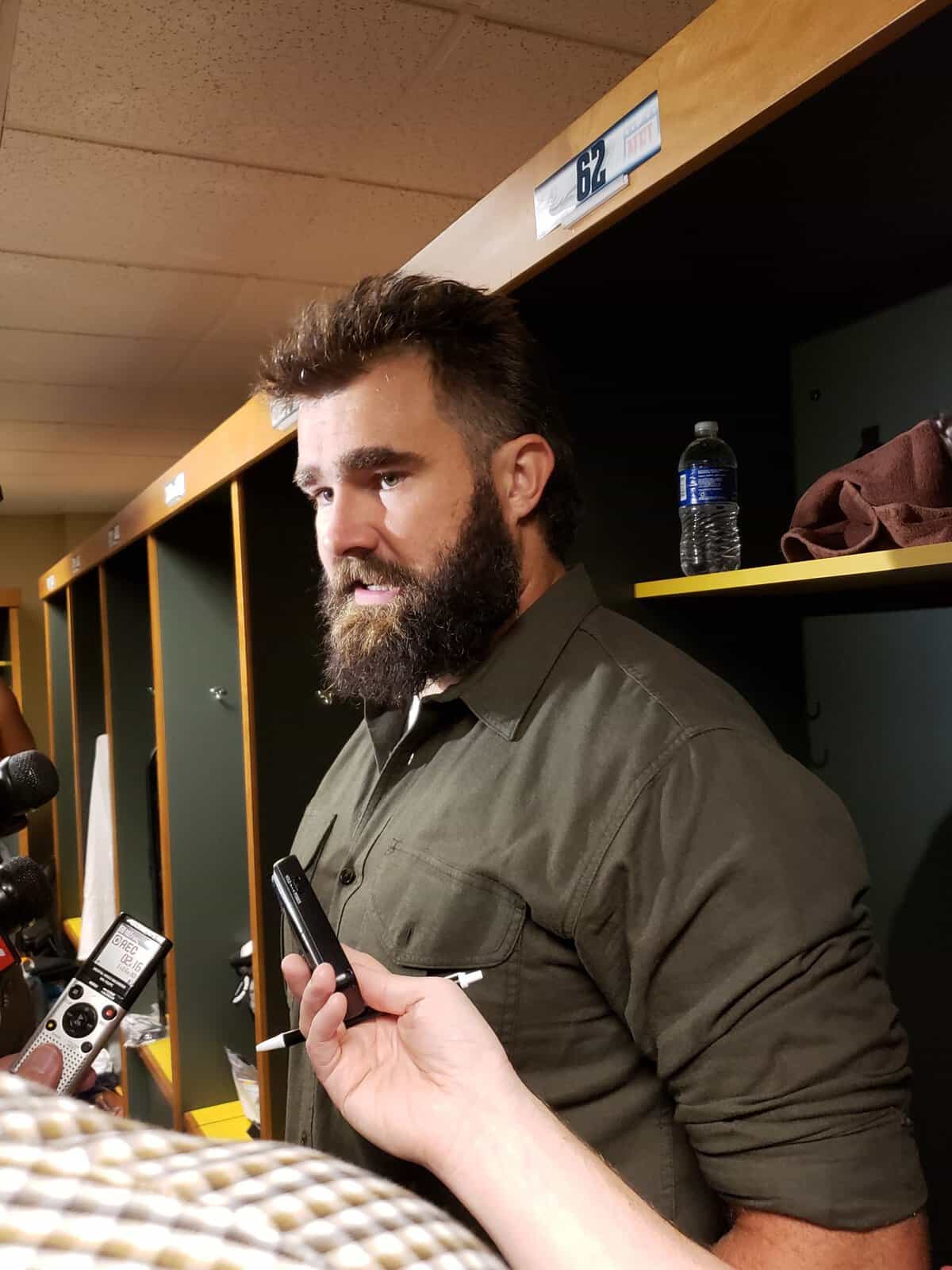

The Damar Hamlin injury has understandably sparked a wave of articles about the violence inherent in football. I’ve spent a good part of my life reporting the Eagles and on pro football in general. I consider myself fortunate in that regard. But I also find myself reflecting on my own tolerance of violence on the football field.

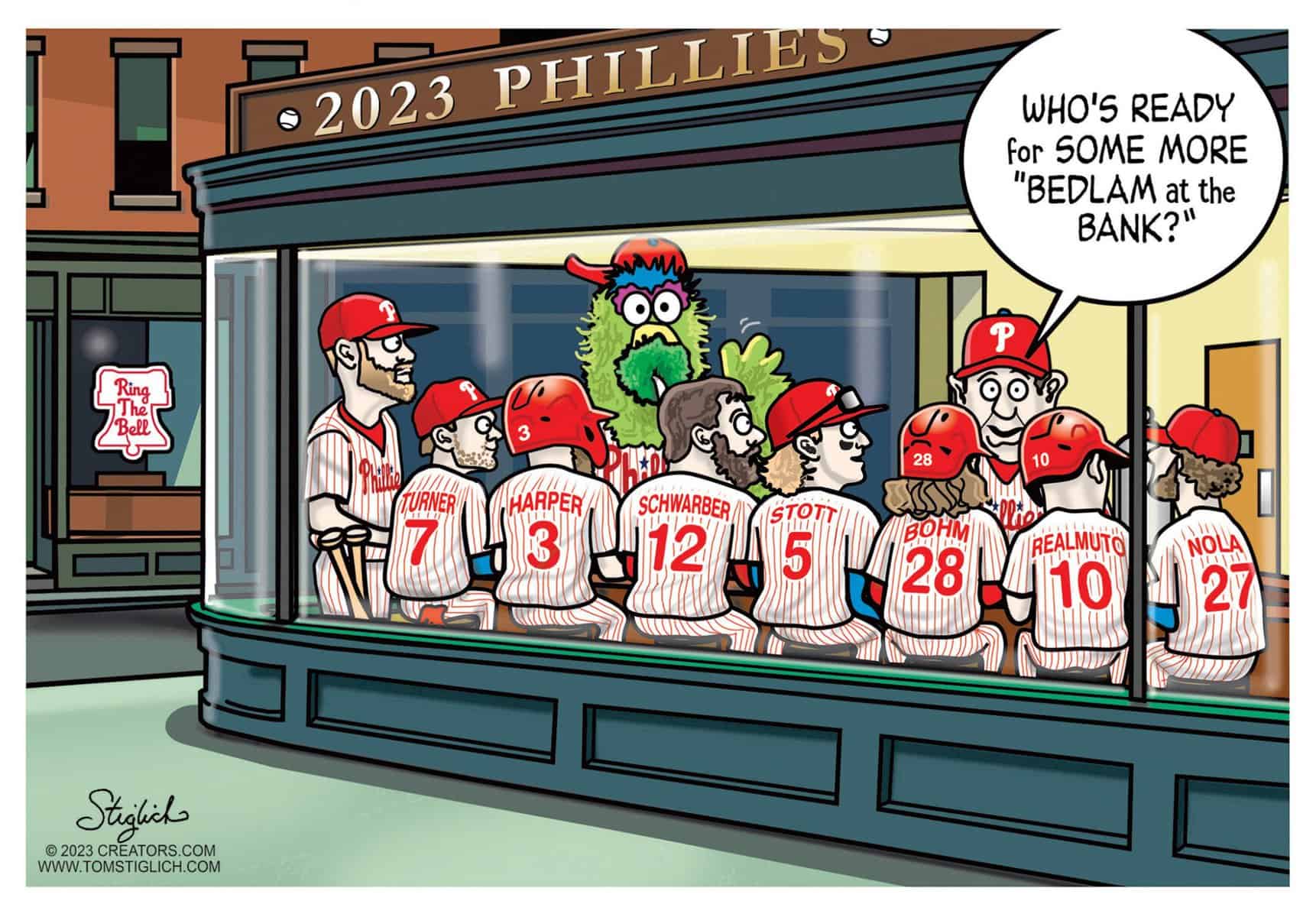

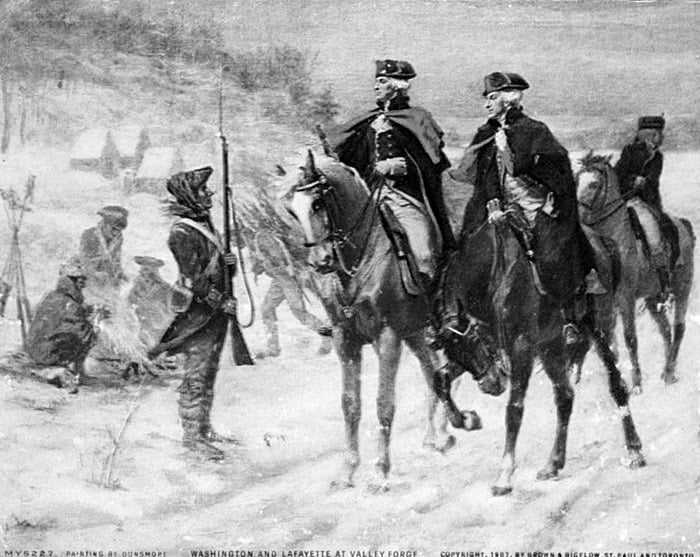

There was a time when baseball was America’s pastime, but no more. By every measure, professional football is this nation’s national pastime and has been since the 1960s. Perhaps the best way to understand the difference between baseball and football is to listen to a skit by the late comedian and social critic George Carlin. In the skit, Carlin explains the different terms used in each of the two sports in hilarious but telling fashion. Football is war. Baseball is a bucolic picnic in the park. I believe that America’s recent embrace of football as its national passion is emblematic of the times we live in. We live in a time of violence. Violence has become the touchstone for us. And when violence becomes routine, we not only become desensitized to it, we embrace it when it happens in a “legitimate” (read:sports) setting.

I don’t agree with those who say we don’t watch football for its violence. That we’ve learned to tolerate that violence, but it isn’t what draws us to the sport. If we’re honest, most of us love the violence. No, we don’t want to see a player get injured. Yet, some folks — a lot of folks — in the stands cheered when Michael Irvin was injured one afternoon at Veteran Stadium playing against the Eagles. Irvin was a perceived villain, so that was OK. The rest of us in the stands laughed at those booing Irvin.

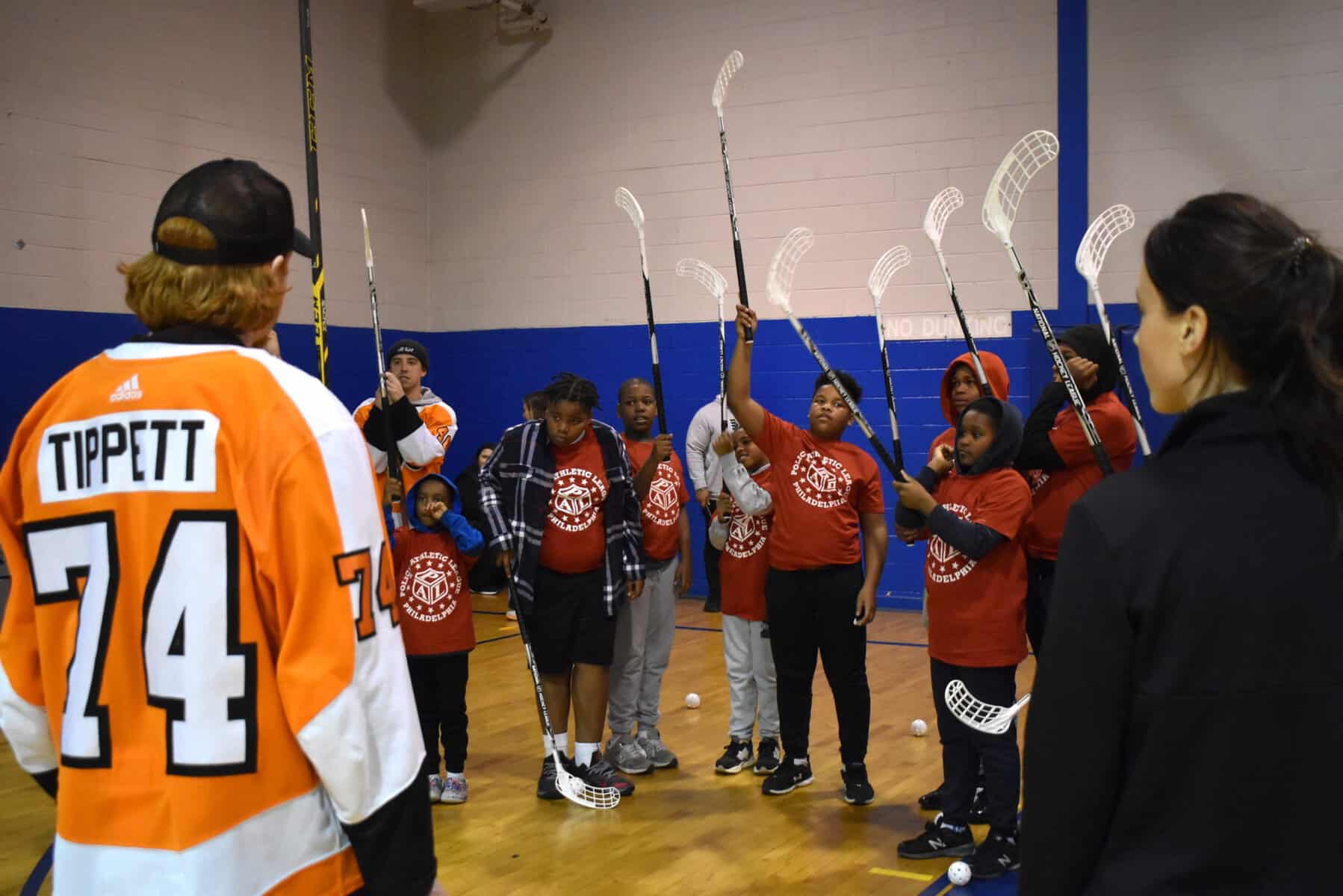

You don’t believe that we — myself included — love violence in our sports? We collect tapes of the big hits. For years, the National Hockey League lived off the violence in its game. Nothing sold then — and maybe now — like a compilation of big violent hockey hits.

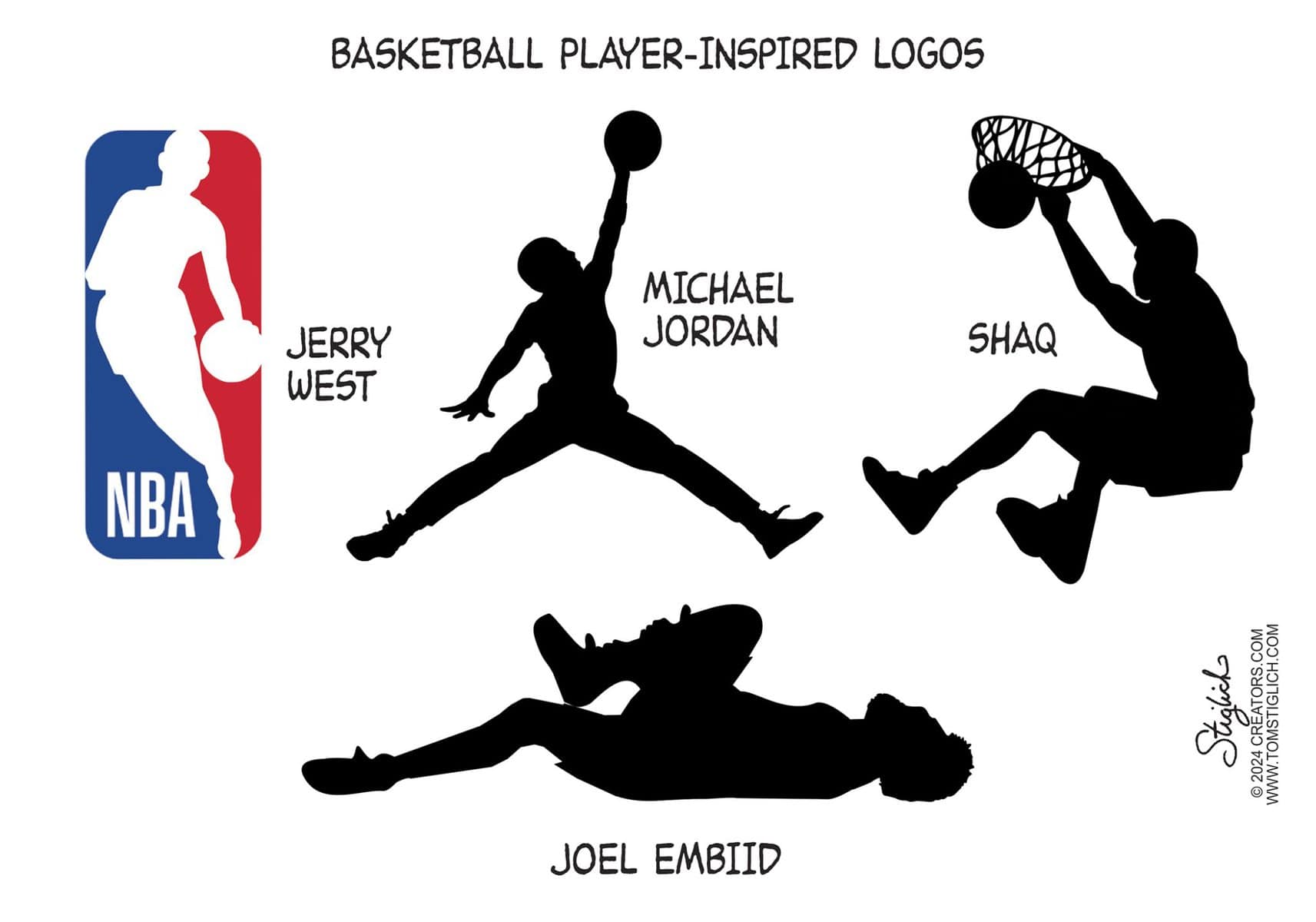

Critics of the National Football League point out that it took years before the league did anything meaningful to make the game safer. The NFL even tried to discredit the medical folks who discovered that football contributed to CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy). When the league acted to improve equipment and change its rules to make players safer, cries went up that pro football was becoming a “sissy” sport. In the same way, when the NHL removed much of the fighting in its game, interest in the game waned. Hell, they’re turning ice hockey into the Ice Capades, some fans and ex-players claimed.

During my years of interviewing Eagles players, I’d always ask them if they would want their kids to play football. I was astounded when most of them — most of them — answered, “No.” Those players were just as fearful as the rest of us of our own kids suffering a serious injury. That’s the thing about most of us, it seems to me, we’re more than willing to see other folks’ kids risk injury to play the game for our entertainment, but not our own.

The plain truth as any player will tell you is that it’s impossible to make football totally safe. Players understand the risks. The collision that endangered Hamlin’s life was legal. Nothing wrong with it, according to the rules of the game. Tragedy has occurred in all sports. Sometimes it finally has brought needed change. In hockey, the use of helmets. It took 50 years after Ray Chapman’s death from being hit in the head by a pitched ball until Major League Baseball made the wearing of protective helmets mandatory in 1970. Due to the nature of the hit on Hamlin, it doesn’t appear that any additional safety measures will be called for. You don’t have to be a violent person to enjoy violence in sports. I’ve been involved in only a couple of fistfights myself — and they were of the brief schoolyard variety when I was a kid. But I loved professional boxing with all of its violence. I cheered along with my parents as we watched Joey Giardello knock the hell out of his opponent — with little or no concern about that opponent’s injuries. I love a good hit on the other team’s quarterback. I don’t think that makes me — or you — a bad human being. Just a human being. Maybe violence is locked into our DNA, looking for a legitimate release.

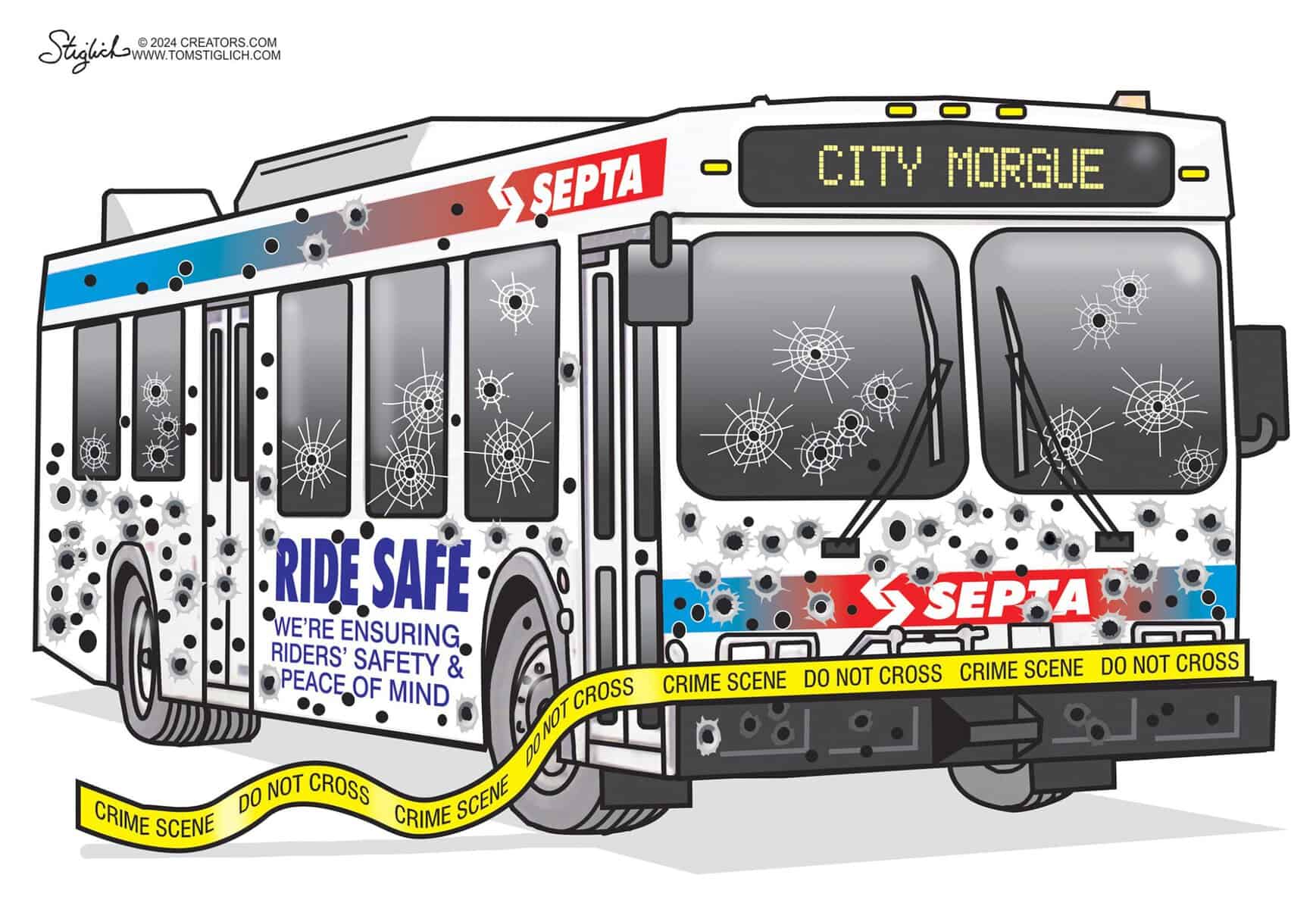

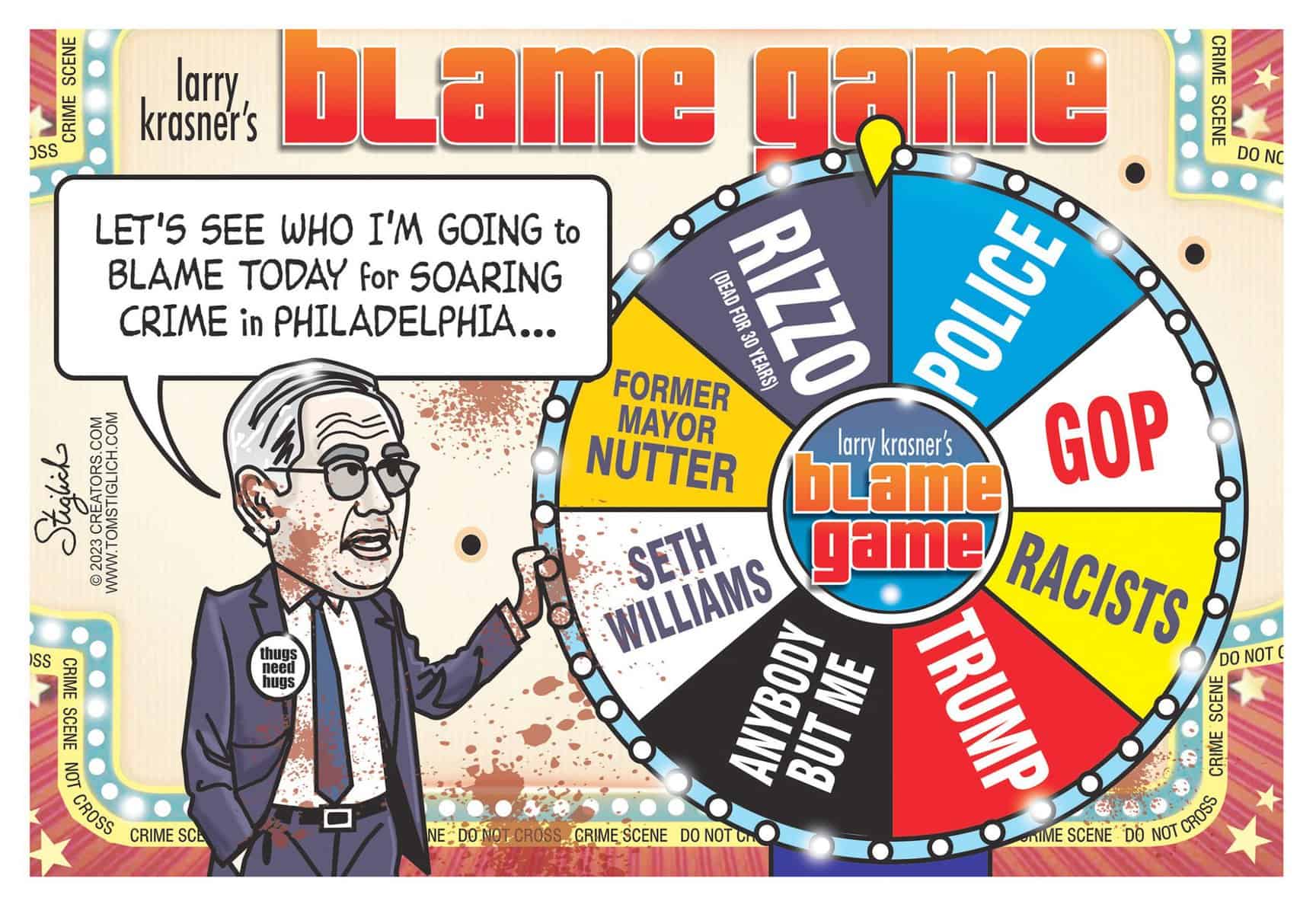

I don’t like that I’m in danger of becoming more desensitized. The horrific events reported every night on the news have become part of our daily routine. Like the weather forecast. The report of the number of homicides is like hearing the scores of games. And how much do we worry about the health of athletes unless it affects whether they can play or not? The recent injury situation affecting Eagles quarterback Jalen Hurts is a case in point. Many of us were critical of his coach for not playing him in the New Orleans Saints game, which the Eagles lost. Our main concern was not Hurts’ health, but the outcome of the game.

I kind of feel sorry for TV sports personality Skip Bayless. Bayless’ immediate reaction to the Hamlin injury was to wonder aloud on Twitter about how it would impact the playoff schedule. Bayless may have a history of being a jerk, but how many of the rest of us had the same thought?

The biggest object to the game being made safer is that most of us like the game just the way it is. We’re a human, often hypocritical paradox. We don’t want the injuries, but we sure love the contact.